The 1918 flu pandemic caused the death of at least 50 million worldwide, with about 675,000 in in the United States, but there is little documentation of its impact in Storrs, with initial reports of the flu arriving in 1919 at what was then The Connecticut Agricultural College, which was closed for the Christmas holiday.

The student newspaper, “The Connecticut Campus,” reported on Jan. 10, 1920 of three deaths — a woman, her daughter, and niece who all lived in the same home. According to the newspaper, the CAC school doctor and nurse conducted daily nose and throat inspections of students. Safety advice for everyone one campus was headlined as “To Avoid Spreading Disease,” and included tips like washing hands with soap and water, using a handkerchief when coughing or sneezing, and only using your own drinking cup.

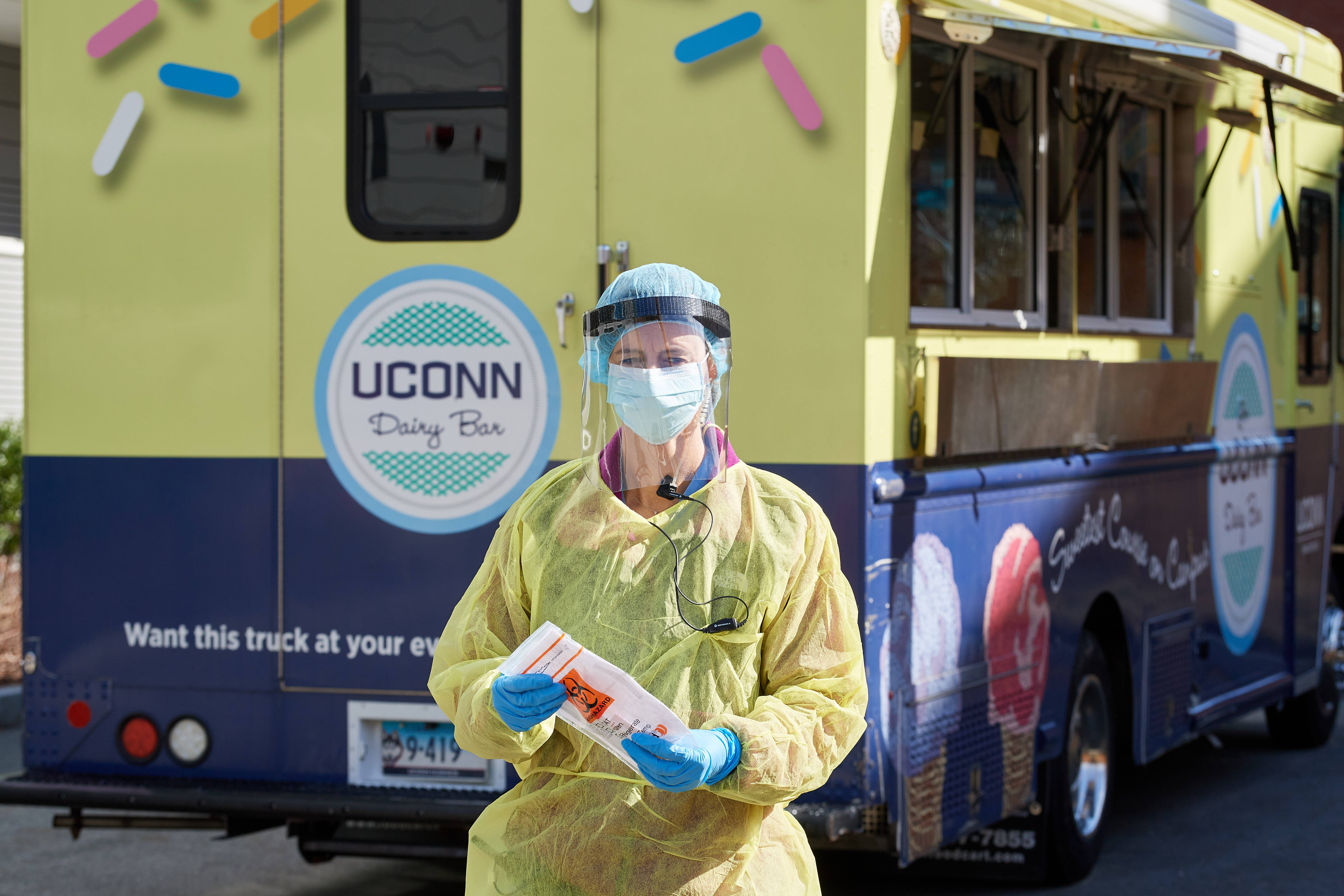

Scholars looking back to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic at the University in 2020 will have a much richer documentary record, thanks to an initiative launched by University Archives & Special Collections (ASC) in the UConn Library.

ASC is reaching out to the UConn community– students, faculty, staff, administrators, alumni, and other affiliated community members– to share their stories of life during the pandemic to be collected, preserved for posterity, and made accessible for research and study in what will be known as the UConn COVID-19 Collection. A website detailing the effort has been established that includes a submission form for members of the University community interested in providing information about their experiences.

“The campus is closed but classes are ongoing, faculty are teaching, alumni are in their own environments trying to work through all this,” says ASC archivist Betsy Pittman, who is leading the documentation effort. “It’s a way to collect personal experiences while it’s happening, rather than in retrospect where things might be colored a little bit differently. UConn is experiencing this in a totally different way, but each one of those experiences are valid. If people are willing to share and have it available for research and study, I’m interested in collecting contemporary documentation of the experiences, reactions and feelings of how people express themselves for faculty, staff, students, and UConn alums as we all adjust, struggle, and move forward through the challenges of a world-wide pandemic.”

She says examples of personal documentation can include audio files, social media posts, emails, screenshots, photographs, blog posts, journaling, zines, interviews, and more. This information will be in addition to the official University information, messages and updates being posted on the existing COVID-19 information website.

Students in three classes this semester are already writing about their thoughts and experiences of how the suspension of classes, concern over the pandemic and disruption of their lives is affecting them, their families and friends. Three professors – Brenda Jo Brueggemann, Aetna Chair of Writing and director of the First-Year Writing Program; Helen M. Rozwadowski, professor of history and maritime studies at Avery Point; and Sylvia Schafer, associate professor of history – revised writing assignments in their courses following the move to online classes to incorporate reflections on the effects of the pandemic.

Brueggemann says during Spring Break in March, she revised the syllabus for her “Advanced Expository Writing” class, creating what she calls the “Quarantine Collaboration Journal.” She asked students to explore writing for a variety of platforms including stop-motion video, infographics, Spotify playlists, a collaborative podcast, a letter, an interview outline, and more.

[See student comments about the journal here]

“It was one major re-making of the course. I just knew this was a moment when writing would, or could, itself become the Hero of Writing,” she says. The course inquiry had been designated as “Writing Identity” and with the new Quarantine Journal assignment, she said, “[The students] could make, shape and record history together as they shared little journal-like pieces and they could set down historically, for themselves and others, their identities in this massive global, national, local moment.”

She adds, “A lot of struggles are being expressed with not feeling comfortable –or even safe –in family/home spaces. Also many feelings of being utterly unmotivated and overwhelmed with the onslaught of carrying out their coursework in isolation from campus.”

In her “History Through Fiction” class at the Avery Point campus, Rozwadowski replaced the final assignment with a new requirement to write both a short story of a post-pandemic imagined future and an accompanying essay, rooted in national media coverage of the pandemic, the kind of document that will be primary sources for future historians to explain how their futurist projections are rooted in fears, predictions, and projections from today.

“I hope that these stories and essays will curate and magnify some of the concerns and hopes of their authors and, thus, might serve future historians,” Rozwadowski says.

Schafer’s students in her “Gender & Sexuality in Modern Europe” and “The Historian’s Craft” classes had the option of writing about the pandemic as part of their class and some did write several times.

“I think many were overwhelmed with an increase in the time they had to spend writing for their online classes, and others seem to me to have been too overwhelmed by the upheaval in their lives to spend time reflecting on it in the moment,” she says. “The students who have written, some multiple times, about what was happening to them, as it was happening, tell unbelievably moving stories.”