The significance of race and far-right politics in the United States played a larger role than previously understood in the shaping of the post-World War II politics in the Cold War, according to a UConn scholar who is studying the origins of the geopolitics of the “liberal international order” led by the U.S. after 1945.

Alexander Anievas, an associate professor of political science and a Humanities Institute Fellow, says racism and ultraconservative anticommunism in the early part of the 20th century following World War I helped to develop American Cold War strategy and “the U.S.-guided formation of a liberal order” in battling the Soviet Union’s efforts to expand its postwar alliances.

He also notes that U.S. intervention into the Russian Civil War following the Bolshevik Revolution that led to the creation of the Soviet Union in the mid-20th century set the stage for future American intervention in other nations.

“The Cold War really begins with that intervention, and it continues throughout the interwar period [between the First and Second World Wars],” Anievas says, adding that it represents what he describes as the “first phase of American Cold War geopolitics,” that included U.S. strategic commitments across the world linked to its Western allies.

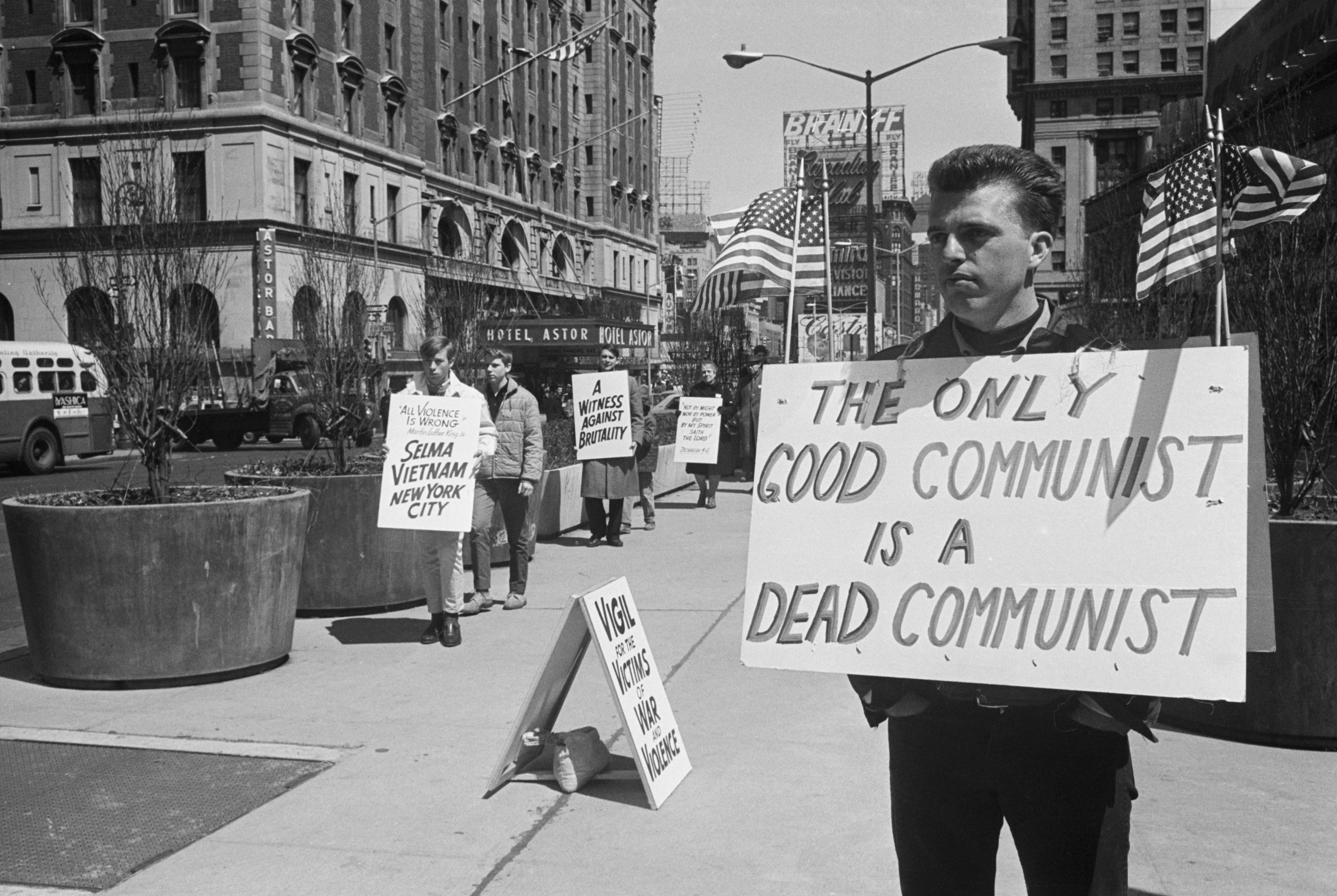

He says the social-political alliance that pushed Cold War policies were rooted in efforts “to incorporate reactionary Southern elites seeking to preserve the prevailing segregated racial order, and often did so in collusion with far-right forces and para-political organizations.”

“I trace the longer history of the influences of the far-right and link it to some of the social forces that were on the rise in the South and subsequently in the kinds of hysterical anticommunism of McCarthyism and the ways in which they fought the emerging civil rights movement, in their own time during the 1930s and 1940s,” Anievas says.

McCarthyism is the period from the late 1940s through the 1950s linked to Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin who made accusations of subversion and treason against private citizens, politicians, the U.S. military and other public figures while conducting investigations.

Anievas also has drawn from his previous writings about President Woodrow Wilson’s role in setting the tone for a new world order after World War I, which he says are rooted in the belief of “a global racial hierarchy.”

During World War I, he says, the Wilson administration tolerated and at times encouraged the formation of vigilante groups that policed the home front against anti-war dissidents, spies, radicals and other purportedly “Un-American” forces. Various business groups often funded such efforts.

“It was based on notions of white supremacy; Wilson was a kind of genteel white Southern supremacist himself,” Anievas says. “His vision of a liberal international order was based on his vision of what a proper society looks like domestically.”

He notes that as the Cold War globalized in the post-World War II period, the political debate was one between “the vital center” and the far-right, which resulted in a strategy fusing containment and rollback that shaped U.S. foreign policies for decades, demonstrated by the decision for American intervention in the Korean War.

“The consequences of these decisions involved nothing less than the permanent militarization of American state-society relations,” he writes in a chapter of the forthcoming edited book, A History of American Literature and Culture of the First World War (Cambridge University Press). “And a vast increase in U.S. strategic commitments across the world that bound the U.S. to its Western allies in a geopolitical order that has lasted until this very day… In these ways, the ‘small war’ in Korea turned out to be a real fulcrum of America’s liberal hegemonic order.”

While some critics of the Trump administration see the results of the 2016 presidential election as a challenge to the core foundations of U.S. postwar policies, Anievas says he saw the rise of far-right politics in Europe that led to the Brexit vote before that election. At the time, he was living in the United Kingdom as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford and University of Cambridge. He became interested in taking a broader, longer view of the impact of far right influences.