Visitors to the Puppet Arts Complex at UConn’s Depot Campus will find that in addition to classrooms, offices, and performance rehearsal space, the largest area of the complex is the workshop where puppets in various stages of design, construction, and completion outnumber visitors, student puppeteers, and faculty.

Fabric, wood, wire, ping-pong balls, closed-cell extruded polystyrene foam – better known as Styrofoam – and other materials can be found in the Puppet Arts Workshop, along with saws, hammers, screwdrivers, and just about any other tool used on an episode of “This Old House” on PBS. Puppeteers make their puppets from a variety of materials based on how they want their puppets to move and perform, using a thought process much like engineers who develop designs for machines, objects, and structures like buildings and bridges.

This similar design process was reinforced for puppeteer and theater historian John Bell when he served from 2007-2011 as a Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Mass., first at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies, and then at the Program in Art, Culture and Technology, which bring together distinguished artist-thinkers to explore art’s complex relationship to culture and technology.

“That experience was eye-opening for me. Puppetry is always designing things and building things and making objects work and mechanisms to make objects work,” says Bell, an associate professor of puppetry and director of the Ballard Institute & Museum of Puppetry (BIMP). “I build things out of wood, paper, and plastics that move on the stage. I realized puppetry is kind of the performance of technology or the performance of engineering. It helped me understand how puppetry and engineering are so deeply related.”

Bell has been exploring that relation in a variety of ways, including a BIMP Puppet Forum moderated by Mehdi Anwar, professor of electrical and computer engineering in the School of Engineering, with historians of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, who focused on the origin of the annual parade’s world-renown character balloons created by Tony Sarg. The balloons are described as “upside-down marionettes,” or puppets, and originally were made of rubber. As the balloon characters became larger and more complex, fabric coated with polyurethane replaced rubber as the core design material.

Expanding on the theme of “Engineering in Puppetry,” Bell moderated a BIMP Forum last fall that further demonstrated how puppeteers use engineering concepts to create and build complex performances, co-sponsored by the School of Engineering and the Krenicki Arts and Engineering Institute, a program of the Schools of Engineering and Fine Arts at the University. The forum was conducted virtually and included Basil Twist, a MacArthur genius grant recipient known for his 2015 underwater puppet show, “Symphonie Fantastique”; Ed Weingart, interim department head of Dramatic Arts and technical director of the Connecticut Repertory Theatre; and Jason Lee, assistant professor-in-residence of mechanical engineering in the School of Engineering.

Weingart and Twist collaborated on the puppeteer’s “Sister’s Follies: Between Two Worlds” production in New York City, staged as a multimedia presentation. Twist said at the forum he wanted to pay homage to the history of the Abrons Arts Center facility, which was celebrating its 100th year, and utilize the orchestra pit, and older parts of the performance structure. He was not planning to use marionettes in the show until a support to hold the weight of actors for a sequence in the show was necessary.

“Whenever I go into a space and there was a catwalk or some sort of setup where you can have performers or puppeteers above the performance space, then you use that. You’d be foolish not to,” he said. “I wasn’t planning on doing marionette stuff, but when we had to build a rig that supported people’s weight, I thought: Oh, I’ll use that. Those are things that you do discover along the way as part of the process.”

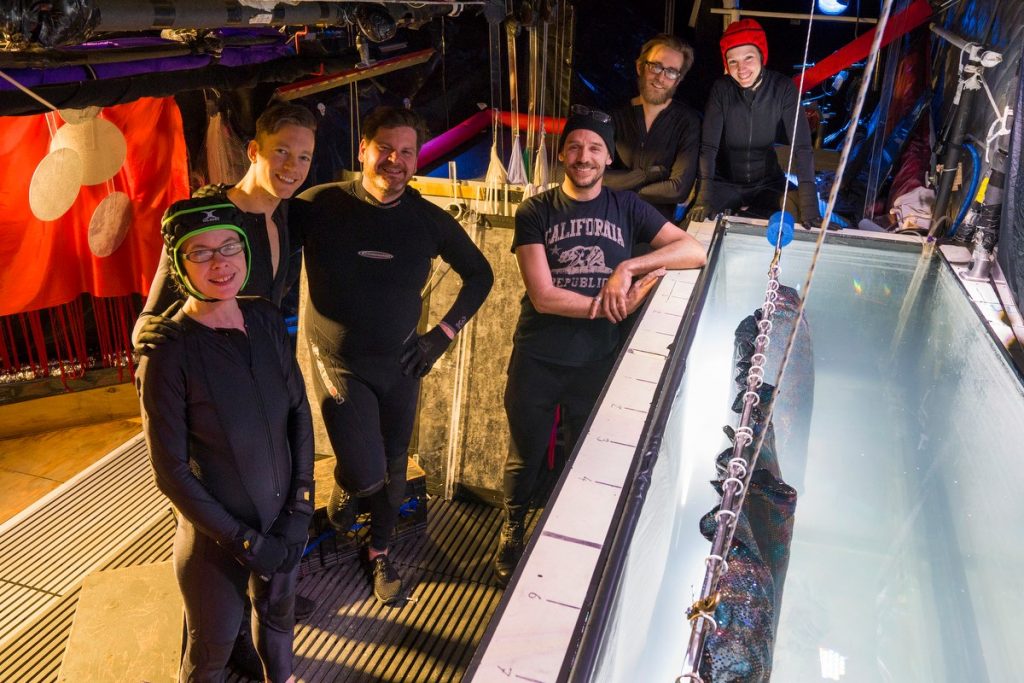

Selecting the proper materials to achieve an artistic effect is also part of constructing a show, Twist said, noting his decisions for “Symphonie Fantastique,” which was performed using a 500-gallon tank of water with the motion of the water a key element of the visual effects.

“We use synthetic materials because they stand up under the water, because it’s the water that creates the movement, not the fabric,” Twist said. “Actually, you can put a garbage bag under water and it looks gorgeous. In fact, if you put silk underwater, it’s not as beautiful because it kind of clumps together so I use mostly completely synthetic materials like a bathing suit would be made out of.”

He said he often uses silk in his creations because it is the lightest weight fabric and provides a lot of movement but that movement is less from the fabric than the “fluid around it, be it the air or the water.”

Weingart, an assistant professor of technical direction in Dramatic Arts, said he describes his work to students as being “an artist enabler.”

“Our job to figure out how to take the vision of artists who often need someone to help figure out and solve some of those challenges,” he said. “I solve technical challenges for artists. I don’t have those sort of visions that really talented artists do but what I do have is the ability to bring them to life.”

An example he cited was working with American sculptor Jordan Wolfson, who created a giant, animatronic puppet in 2016 that is now at the Tate Modern Gallery. The puppet was more than 7-feet tall and was manipulated by very large linked chains. Weingart initially tried to reduce the size of the chain, similar to that used with a boating anchor, more than an inch thick, to go between the puppet and the mechanism used to move the puppet. However, it did not work.

“It had to be that size chain, that to fulfill this vision. So we had to go back and basically make everything from scratch and make a machine that was able to move both very slowly, but also be able to drop the puppet at almost the speed of gravity,” he said. “It was really a unique, interesting engineering challenge because no machines like that exist in the world. There are chain hoists that do lifting with smaller chains very slowly and there are the anchor systems on mega yachts, which work completely differently. We had to mash those two things together and then create something that would be safe for the audience and safe for the creators to work around.”

Lee said the similarity in puppet design and engineering is that both disciplines approach problem solving in the same manner by considering the same questions:

• What materials should you utilize?

• What process is needed to manufacture the components?

• How will you put everything together?

• How will you control it? Strings/Hand/Mechanical Actuators?

• Will it be functional after repeated use?

“But one big piece that’s probably differentiating is that creativity, that storytelling to aesthetic component,” Lee said. “We talk to our students about, how do you pick the materials, how strong is the material, how’s the material interacting with the environment? It’s very seldom that we really think about how nice does it look, what colors do we choose, how does the light bounce off of it? That’s an aspect of design that we typically don’t see, but I can imagine that the design process would be quite similar. “

The Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry is open on a reduced schedule and timed entry during the pandemic on Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. by reservation only. Puppet shows and Puppetry Forums are being conducted virtually. For information about exhibits, performances and Puppetry Forums go to www.bimp.uconn.edu.