Sharing stories over a cup of coffee; dancing in a group; cheering a football game in a crowd: these everyday rituals are among many different types of shared experiences that help humans develop social cohesion.

UConn researchers are studying another way humans connect: through synchronous movement or chanting, and Mohammadamin Saraei, a graduate student in the Department of Psychological Sciences, says we can see examples of the phenomenon everywhere around us, and throughout history in many cultures and religions. After years of research, we now know that synchrony enhances social cohesion, creates a shared identity, boosts prosocial behavior, builds trust, and even contributes to our overall well-being.

But what makes this group-level synchrony happen? Saraei and co-authors Alexandra Paxton, assistant professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences, and Dimitris Xygalatas, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology, have detailed their findings in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

The researchers studied synchrony during a religious ritual at the UConn Islamic Center, called Salat al Jama’ah, where more than 200 worshipers gathered for evening prayer. The researchers wanted to determine which aspects of the ritual were most impactful for creating synchrony, so they recruited participants who agreed to wear a comfortable device to measure physiological data like heart rate, breathing, and posture, and another device to measure the position of the participants throughout the prayer.

Saraei says that each day there are five rounds of prayer that Muslims are advised to do, and ideally with others as a community. To emphasize the community aspect, the researchers timed their study during the holy month of Ramadan, when Muslims fast during daylight hours and are likely to pray in larger group settings.

“We are very appreciative of Muslim students at UConn because it was difficult to participate in this study, especially considering we gathered this data during Ramadan, when they were fasting for 14 hours or so, but they were very cooperative and this study would not have been possible without them,” says Saraei.

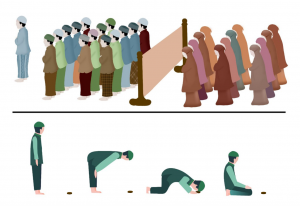

For the ritual, worshipers gather for the group prayer, and men are encouraged to line up closely behind the leader (imam), women usually gather behind a partition, and everyone faces the same direction – qibla, or the direction of Islam’s most holy site in Mecca. The imam leads a cycle of prayers which include coordinated sequences of bowing and prostrating movements.

The results showed that, beyond impacts from worshippers around an individual, the researchers discovered the important role of the leader in creating synchrony and its physiological impacts, like synchronization of the participants’ heart rates.

“This study shows us the important role of a leader in a community. Having a leader is a double-edged sword. This role can either be beneficial or harmful—because if you have a bad leader, they might create a toxic environment for everyone, like in a cult. But if you have a good leader, they can foster a community that helps everyone grow,” Saraei says.

He says another important aspect of creating synchrony was the effect of proximity the worshipers had to the imam — the closer to the imam, the stronger the effect.

“Worshipers are strongly advised to go to the first lines behind the imam. We don’t know the religious reasons behind it, but, interestingly, it is connected to the synchrony measures we have too,” he says. “I think one of the most important findings of this study was that if you are closer to that center of synchrony, you will get more synchronous, even physiologically in your heart rate, and there seems to be a ripple effect to the lines behind.”

This ripple effect is likely due to the auditory-visual information that worshipers receive, says Saraei. During the prayer, people are looking down, therefore they can see their nearest neighbors in their peripheral vision, and this seems to help with coordinating movements.

“They hear the imam, but some of them do not see him, and there is a kind of two-way effect of synchrony. On one hand, you’re seeing your neighbors, and this is one of your major sources of information, but on the other hand, you’re affected from a longer distance by the imam.”

Beyond religious settings, Saraei says Xygalatas’ research group is also looking at the role synchrony plays in political events like debates or rallies.

“The way people chant or clap for the president, these gestures all affect social cohesion. Another example is with soldiers marching, which is no use in today’s battlefields, but marching still makes sense because it helps create that bond you need on the battlefield.”

Saraei is currently analyzing other positive health benefits of synchronous prayer by looking at heart rate variability (HRV) during prayer.

“Another interesting finding in my current analysis is the increase in HRV during Islamic collective prayer, suggesting its positive effects on well-being and stress reduction.”

He says HRV is an indicator of things like reduced stress, a greater sense of well-being, and a healthy immune system. Saraei also has plans to investigate how the number of participants impacts synchrony and the potential impacts of virtual versus in-person participation.

Saraei says this study shows some of the mechanisms underlying synchrony for grounding and creating social interactions and cohesion. This is important because synchrony is a key aspect of our social lives.

“Synchrony is all around us, subtly shaping our connections and experiences,” says Saraei. “Once you recognize it, you begin to see it everywhere, woven into the fabric of daily life—bringing us together in ways we often take for granted.”