Plastic pollution has become a global crisis, with the United Nations Environment Programme estimating between 19 and 23 million tons of plastic waste leak into aquatic ecosystems each year. A partnership between UConn marine sciences researchers and a leading bioplastics manufacturer is showing promise in addressing this issue.

A recent study published in the Journal of Polymers and the Environment found that Mater-Bi, a starch-based polymer produced by Italian company Novamont, degraded by as much as nearly 50% over nine months in a marine environment—significantly more than traditional plastics.

Novamont, which has a U.S. office in Shelton, collaborated with the UConn team to evaluate the product’s biodegradation.

The study was led by Hannah Collins, a marine sciences Ph.D. candidate. Collins and her co-author, Larissa Tabb ’22 (CLAS), highlighted research done as part of the Marine Environmental Physiology Laboratory under the guidance of her advisor, professor and head of marine sciences Evan Ward.

“I’ve always been interested in how marine animals interact with their environment,” Collins says. “When our lab started looking at microplastics, it was clear how pervasive and damaging this problem is.”

Collins says the findings could have meaningful implications for reducing plastic pollution in aquatic environments. For example, products like Mater-Bi could replace traditional plastics used in aquatic structures, such as kelp farm lines, to reduce the possibility of plastic pollution.

“We’ve seen the pictures of sea turtles with plastic around their heads,” she says. “We have a lot of evidence of the negative effects of plastic pollution.”

Collins, who grew up visiting Cape Cod and the beaches of Long Island Sound, has long been fascinated by marine life. After earning a degree in biology from Gettysburg College and working in Alaska’s salmon fisheries, she decided to combine her passion for marine organisms and the environment, first in her master’s program and now for her Ph.D.

She says the collaboration with Novamont has helped her feel like she is making a difference in addressing marine pollution. It also provided her with hands-on experience examining real-world product applications.

Biodegradable plastics like Mater-Bi degrade much faster than traditional plastics, reducing risks to aquatic environments. However, Collins notes that many of these products are often tested under controlled conditions, not in real-world marine environments.

Students spent nine months monitoring degradation of Mater-Bi

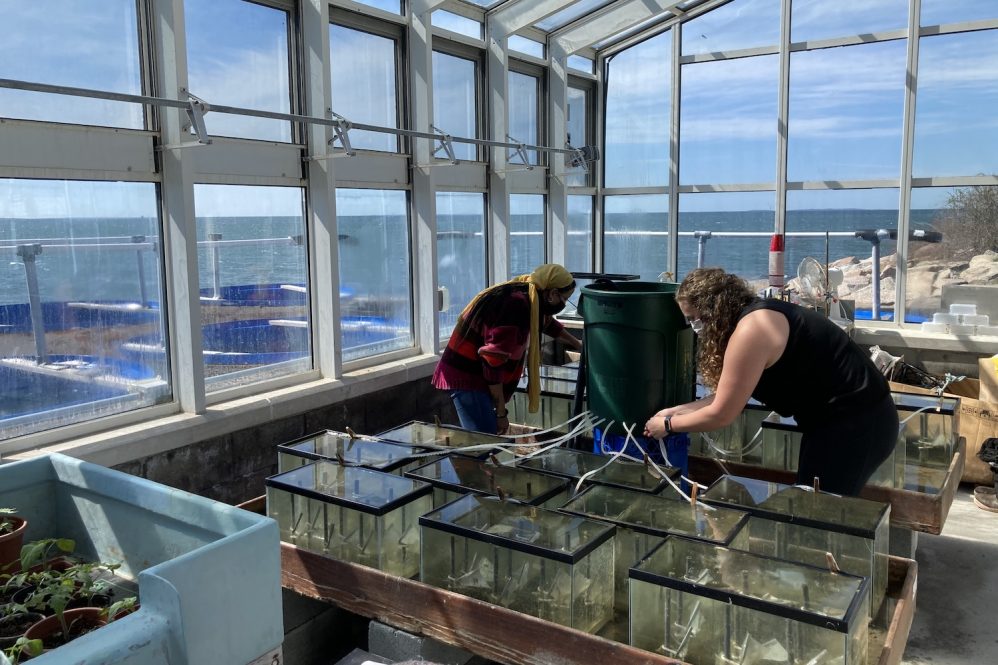

Collins’ research on Mater-Bi was conducted in a semi-controlled environment at the John S. Rankin Laboratory on the Avery Point campus. The lab filters seawater from the surrounding area to keep large organisms, like crabs, out. This allowed Collins and her team to test how much the product degraded in natural conditions while ruling out the impact of interference from those large organisms.

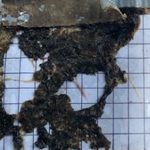

Her team tested samples of a Mater-Bi compostable bag, a traditional plastic bag, and a known biodegradable plastic in the lab. Every two weeks, they checked and measured how much each sample degraded by either mass or area. After nine months, they found that the Mater-Bi samples lost between 25% and 47% of their mass or area. Additionally, they found that the rate of degradation increased during warmer months.

“Microbial activity tends to increase in warmer conditions, which likely contributed to the faster degradation rates we observed,” Collins says.

Collins says she is hopeful that these findings could lead to future uses of Mater-Bi in aquaculture, especially for products where temporary or disposable materials are often used, such as oyster grow-out bags or kelp farming lines.

“If something breaks loose, it won’t persist in the water for decades,” she says.

Collins and Tabb have maintained connections with Novamont. Collins will attend the World Aquaculture Conference in New Orleans this March, where she hopes to connect industry leaders with biodegradable products like those produced by Novamont.

“Addressing plastic pollution requires a range of solutions,” she says. “Biodegradable plastics are just one piece of the puzzle.”