Almost every night of the last four years, Ana María Díaz-Marcos says her family half expected Ernestina to come for dinner.

Even after long train rides home from New York City where she’d spent the day hunched over research materials in the NYU library, Díaz-Marcos says Ernestina would make an appearance at the table.

Those were the times, in fact, she’d most certainly show up.

Ernestina González Fleischman and Díaz-Marcos have been almost inseparable since the two met accidently in 2021, when Díaz-Marcos came across her name in a December 1937 issue of La voz, a Spanish newspaper published in New York City between 1937 and 1939.

It was a serendipitous meeting that arguably changed both their trajectories.

Díaz-Marcos, a Spanish professor in UConn’s Department of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages, says the rest of her career likely will be dedicated to projects like the one about Ernestina.

And Ernestina, born in 1896 and died in 1976, may very well, at least after publication next year of the biography that Díaz-Marcos has penned about her life, finally get a Wikipedia entry – maybe even a movie.

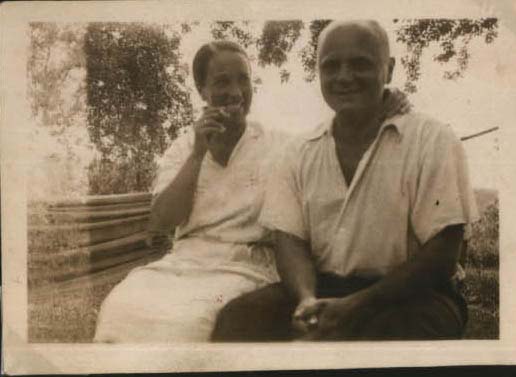

Because the story of Ernestina and her husband Leo Fleischman is colorful enough for the silver screen. It’s one of bravery, exile, tragic love, sorority, espionage, and activism during a time when the Spanish Civil War shaped their lives.

‘So powerful and so committed’

In 2021, Díaz-Marcos says she was doing research in La voz for a digital humanities project on feminism and antifascism. She’d arranged with the New York Public Library, then closed during the pandemic, to get PDFs of the paper’s women’s page sent to her, so she could continue her work.

In one of those packets, the headline “Mujeres a la Lucha,” or “Women to the Fight,” caught her attention, she says. The article opens with two words – Ernestina González – and goes on to talk about a speech she gave before a packed theater and her thoughts on the responsibilities of Spanish, Hispanic, and Latina women in the city at that time.

“It was so powerful and so committed. I mean, the words are on fire,” Díaz-Marcos says of the speech. “I couldn’t believe I never heard of her, not a single word, and I’m a feminist scholar.”

With her initial project wrapped, Díaz-Marcos says she turned toward Ernestina, finding only a small article about her and her sister, who were both librarians born in Burgos, Spain.

Then more digging uncovered an April 1938 photograph from the Library of Congress depicting a crowd of 3,000 women who’d traveled by train from New York to Washington, D.C., to urge the neutral United States to support Republican Spain in its civil war with the Nationalists lead by Gen. Francisco Franco.

The photo’s cutline says, “The widow who headed the delegation was Mrs. Ernestina Gonzales, PH.D., and former Director of the Madrid University Library.”

Díaz-Marcos says she thought González’s efforts – after all, she’d mobilized thousands of women to march on the National Mall – merited at least some academic attention. But she started digging and couldn’t stop.

“Ernestina was one of the most important activists in New York from 1937 when she moved there after her husband was killed until 1953 when she fled to Mexico during McCarthyism. Even then, she was advocating nonstop against Franco, fascism, and colonialism. She never stopped,” Díaz-Marcos says.

During those 20 years in New York, Ernestina published work as a journalist in Spanish language newspapers and directed a radio program, all while conducting grassroots activism against the Franco regime.

Surveilled for 20-plus years

Ernestina came to the U.S. in 1926 as a Spanish lecturer at the University of Lincoln in Nebraska, Díaz-Marcos says. Her FBI file – oh, that’s right, she has two dossiers totaling 1,500 pages – indicates her contract wasn’t renewed because she didn’t fit what the school was looking for.

Despite her 5-foot-3 frame, she was a firecracker – liked to party, smoked on campus, cut her hair into a bob – and the students gossiped about her, according to the department chair who the FBI interviewed as part of its surveillance of her.

The FBI file places her in New York by 1929.

Díaz-Marcos says she got the idea to request the file after talking with a colleague, who also had a fellowship with the UConn Humanities Institute last year, about making freedom-of-information requests.

She knew Ernestina moved in leftist circles and had been interrogated by the House Un-American Activities Committee, so it was reasonable to assume there might be a file. Turns out, she was under heavy surveillance.

“They were covering her mail. They were talking to the janitor, the superintendent, and the postman. Everything is documented in a declassified document of 600 pages that I received,” Díaz-Marcos says, explaining the rest of the file was archived in Maryland and not readily accessible.

“She was under surveillance for more than 20 years, even into her second exile in Mexico,” she goes on to say. “The FBI had all her associates under watch not because of what was happening in Mexico, but the implication it would have for Soviet espionage or communism in the United States.”

Not to mention that her sister was living and raising a family in Moscow.

But before any of this, Ernestina met Leo, cousin to the Fleischmann yeast family and nephew of Minnie Untermyer, a prominent New Yorker whose husband Samuel was the first American lawyer to earn a $1 million fee on a single case. He gave the estate in Yonkers, New York, that today is the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy.

Díaz-Marcos says she doesn’t know exactly how the two met, or precisely when. She managed to discern that Ernestina was taking English classes in New York for a summer and had a friend who got engaged to a wealthy American who was Jewish.

It’s possible this woman’s family and the Fleischmans were connected through their social circle, thus bringing together Ernestina and Leo. It’s also possible the two came together because they both spoke Spanish; Leo had spent time in Peru as a mine engineer.

She does know they married in 1932 and moved to Ernestina’s home country of Spain the following year.

Together with her sister and brother-in-law – who were living in Spain before exile divided the family between Moscow and Mexico City – Ernestina and Leo supported the Asturian Revolution in 1934, feeding information to the French press and helping refugees of the fighting, all the time moving in leftist groups.

“In 1936, four years after they were married, there was this coup d’etat in the north of Africa and the war starts,” Díaz-Marcos says. “Leo immediately joined the 5th Regiment and started working in a munitions factory to manufacture weapons. And that’s the tragedy of the story. He was working in the factory and there was an explosion.”

Leo died in October 1936, the first American killed in the Spanish Civil War.

“Ernestina always maintained that it was sabotage,” Díaz-Marcos says, explaining the newspaper beholden to the opposition reported on the blast even before it happened. “She dug in and resolved to devote her energy to antifascism, to the cause that he died for.”

On Christmas Eve 1936, only two months a widow, she landed in New York City and took up residence with Leo’s mother, Pauline – herself outspoken against Nazism – until Pauline died in the early 1950s.

“Ernestina and Leo were very intrepid and adventurous, and they put everything into what they believed in. Both would have witnessed poverty at different times in their lives. They saw that in Spain and here during the Great Depression, and their social consciousness awoke,” Díaz-Marcos says. “They wanted democracy and social justice.”

Leaving a legacy

Ernestina never remarried and she and Leo never had children. Most of her siblings were unmarried and also without children, except her sister in Moscow who had two sons, one of whom had children. Díaz-Marcos says she believes Ernestina’s brother may have fled to Cuba, so it’s possible some family members are there.

Leo was an only child, so any living relations would be extended family members, that is distant cousins and aunts or uncles with one or two greats before their names. This means few people alive today would have met or have memories of Leo and Ernestina directly.

“This kind of story reminds us that everyday people can have such an impact in many ways, but it’s easy to be forgotten. When Ernestina passed away in 1976, it was too early for historical memory,” Díaz-Marcos says.

That’s why for her, telling Ernestina’s story is important.

She wants people to understand that even someone who’s unassuming can have a profound effect on the world around them. Even a quiet librarian who started out as an academic can triple in size by the effects of their actions.

“She doesn’t explicitly say ‘I am a feminist,’ but she’s always talking about the role of women. How no war, no revolution, no progress can be achieved without women taking part,” she says. “She was a feminist in that sense. And I hope I’ve done justice to her story.”

Ernestina and Leo are buried together in a civil cemetery in Spain, with a small plaque marking their gravesite. “In grateful partnership,” it reads.

Today, Ernestina doesn’t come up for discussion as often around the family dinner table at Díaz-Marcos’s house. Another woman has taken her seat, as the professor moves onto her next project. She’s a friend of Ernestina’s, the head nurse who traveled with the first American health care team to Spain during the civil war.

“I think the rest of my life is going to be dedicated to this kind of work,” Díaz-Marcos says. “Stories like this are for everyone.”