As comfortable as Molly James is talking about tidal data depicted on a linear graph, she’s equally at ease discussing the differences between mere sonification of those data points and the musification of what those points convey.

“Making it sound pretty, I think is the difference,” the Ph.D. candidate in oceanography says.

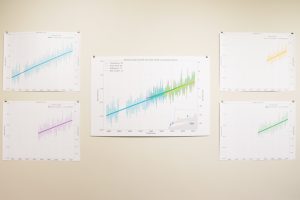

James points to a graph of tidal data from The Battery, New York, which dates to 1856 and shows a progressive rise from 15 inches below the mean sea level to about 5 inches above it today.

One could imagine a pianist playing an ascending passage up the keyboard in simulation of the data, she says. It’s a simple rise in pitch – do, re, me, fa, so – not really music, pure sonification.

Now bring in a composer to add musical components to those scientifically derived notes, things like scales and harmony and dynamics. The result, James says, still conveys the phenomenon of sea level rise and accounts for those data points but does it in a way that evokes emotion and captures a listener.

Sonification vs. musification – that’s the biggest difference between the first part of James’ “Harmony of Nature” project and the latest, funded by a 2023 Arts Support Award from Connecticut Sea Grant.

‘Exercise in science communication’

“Harmony of Nature II: Waves” adds Julliard School graduate and composer Maxwell Lu to the team of Hea Youn “Sophy” Chung, a Julliard-trained pianist from South Korea, and James, an oceanographer from UConn’s marine sciences department.

James and Chung met through a mutual friend about 10 years ago, reconnected during the pandemic, and developed “Harmony of Nature” several years ago as a collaborative effort with support from the Arts Council of Korea. In short, the two wanted to find a way to connect their expertise – oceanography and classical music.

The project’s success encouraged them to keep going, James says, and look for a composer to help with the musical arrangements, which Chung found in Lu during a visit to her alma mater.

Now a team of three, James says Part 2’s “Waves” started with a lot of discussion about what natural phenomena to feature and what data would make for interesting pieces. Was there a storm or storm-related event they felt was noteworthy?

“That’s where it shifts to my focus of acquiring the publicly available data, analyzing it, researching, presenting, and communicating to the two of them,” James says. “This project is a constant exercise in science communication for me.”

If that communicative piece lacks, she adds, the resulting arrangement lacks too.

“So often these fields are siloed, and they don’t talk to each other,” she says. “Science and art, they’re taught in separate ways. You take a science class, you take an art class and rarely do they intersect. But [as you go through life] these overlapping ideas, you see them more and more. You see the patterns in science that you see in art and music.”

The nearly nine-minute piece “sea level rise” from “Waves” uses data from four long-term tide gauges maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in The Battery and Kings Point, New York, and Bridgeport and New London, Connecticut, James says.

Scientists need at least three decades of measurements to detect sea level rise, she explains, noting that the Connecticut Institute for Resilience and Climate Adaptation projects a rise in Connecticut of about 20 inches by 2050. Over the entire time series, The Battery’s data shows an increase of about 1.14 inches per decade, or about 4 inches above mean sea level today.

Lu’s interpretation as performed by Chung is a meandering piece, slow to start, haunting in the middle, with increasing intensity around the six-minute mark through the end, or what a listener might recognize as the last 40 years of more than 150 years of recordkeeping.

Their “honshu_east_all – tsunami,” by contrast, is a four-minute musical interpretation of the tsunami that caused the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan in early 2011. The bell tones two-thirds of the way through are deliberate sonifications of the tsunami from buoy data and evoke mental images of the mass casualties and extensive destruction wreaked by the disaster.

“It’s pretty jarring, and that’s one of the reasons we chose it,” James says of the natural phenomenon, explaining the data came from 11 Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis, or DART, buoys from NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

The Tohoku earthquake, a 9.0-magnitude quake in the Pacific Ocean just off the east coast of Japan, moved the Earth’s crust, James says, causing the water above it to be displaced.

The DART buoys recorded a displacement of about a meter, or 3.3 feet, of water in the open ocean, she continues. As that water moved toward land, it piled up, causing a tsunami that measured close to 40 meters, or 130 feet, high when it crashed into Japan’s coastline.

‘A project in perpetuity’

While the energy of a tsunami is something that makes for a dynamic musical composition, James says the team isn’t averse to one day highlighting the data points of a rainbow or sunny day. Not everything in nature is doom and gloom, she acknowledges.

And that means they’re already thinking about Part 3 of “Harmony of Nature.”

“This is a project in perpetuity,” James says.

“Waves” culminated with a performance in early April during the opening reception of two art exhibitions at the Alexey von Schlippe Gallery at UConn Avery Point, “Seaward: Coastal Paintings by Jacqueline Jones and Mary Temple” and “Harmony of Nature II: Waves.” The latter put on display some of the scientific data used in the album’s composition, alongside Lu’s music and Chung’s margin notes.

“There’s a lot more in common between STEM fields and humanities and arts fields than a lot of people recognize,” James says. “Music theory is a lot of math; it’s a lot of relationships between frequencies that we happen to hear through a piano note or a trombone.”

More practically, physical oceanography uses acoustics in its everyday work, she continues. An acoustic doppler current profile literally sends soundwaves into the ocean to measure the speed of water.

“I’ve played tuba and trombone from high school into college and now in a community orchestra,” James says, and “90% of the low brass section I’ve played with are scientists and specifically physicists. There’s so much connection between music and science.”

The beauty of turning science into music is being able to capture an audience of people who might loath linear graphs, plot points, and measurements. Through sound, they too can learn about and understand a concept like sea level rise.

“One of our goals is to be able to reach the nonscientist with scientific concepts and communicate those, and music is … [a] medium where it’s incredibly accessible to people, so if we’re able to merge these things together and create connections between the fields, then we can reach a greater audience,” James says.