When it comes to the best way to repair a dislocated shoulder, the answer, like so many things in modern medicine, has evolved from “open surgery” to “minimally invasive surgery” to “it depends.”

“Now we have open techniques, we have arthroscopic techniques, we have bone grafting techniques, and any or all of these procedures may be available to any patient at any one time, depending on the degree of instability, the amount of damage to the ligaments and the labrum and the bone,” says Dr. Robert Arciero, orthopedic surgeon and chief of the UConn Health Department of Orthopedic Surgery Sports Medicine Division.

The discipline of orthopedic surgery is moving in this direction – a well-defined understanding of which techniques work in the vast majority of cases and an acknowledgement that there often are multiple factors causing shoulder instability.

“The surgeon must treat all of the problems that are treating the shoulder instability, or the surgery will fail,” says Arciero, who is one of the team physicians for UConn athletics. “And I think that’s why we’re seeing some increased failures, particularly in young athletes.”

For example, the minimally invasive arthroscopic approach is appropriate when soft tissue repair is all that’s needed to stabilize the shoulder. And surgeons still can use the scope to restabilize the shoulder even when damaged ligaments, labrum, and bone are all culprits. But that’s where it gets dicey – That soft tissue repair doesn’t address the damaged bone, setting the patient up for recurring instability and additional surgery.

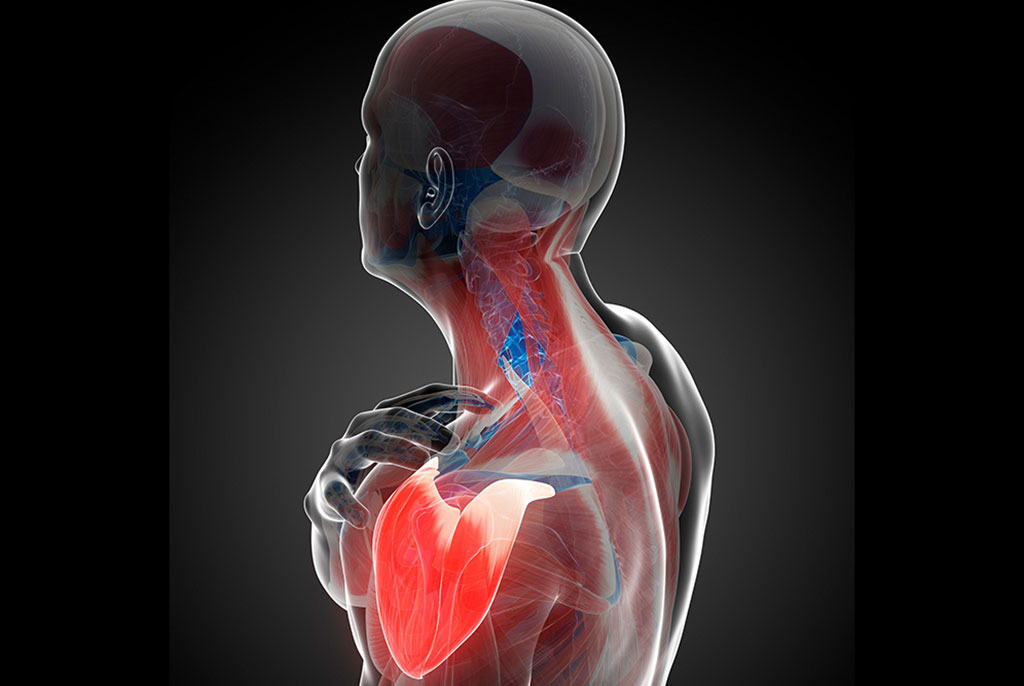

As a ball-in-socket joint, the shoulder can be likened to a golf ball on a tee. Picture the rounded top end of the humerus (the bone in your upper arm) as the ball, and the cup-like socket of the shoulder blade as the tee. If there’s bone damage, it’s like the corner of the golf tee is worn down to the point where the ball doesn’t reliably stay on the tee anymore.

A patient with multiple dislocations due to torn labrum and ligaments can start to wear down the bone. And it’s in those cases where a scope alone isn’t enough.

Those cases also are leading surgeons to believe that often it’s better to intervene earlier than what historically has been done – before the additional damage occurs, and perhaps as early as after the first dislocation.

“Here at UConn we have surgeons who are studying this problem their whole career, and developing and defining not only the surgical techniques, but what patient needs what procedure,” Arciero says.

Sometimes that means a patient who had a shoulder repair done elsewhere will end up at the UConn Musculoskeletal Institute for another surgery because the technique used the first time either failed or didn’t fully address the problem.

In all cases, the patient’s chance at success greatly increase when the surgeon embraces this new way of thinking, understanding that the one procedure he or she was trained to rely on is not always the best approach.

“The better outcomes are when we are able to appreciate all of the problems that are causing that person’s shoulder to be unstable, and then we fix all of the problems,” Arciero says.

Learn more about orthopedics and sports medicine at the UConn Musculoskeletal Institute, or call 860-679-6600 to schedule an appointment.