The American Medical Association is acknowledging the growing evidence of health problems associated with exposure to artificial light, and is taking action that could lead to more government funding of research in this area.

The AMA’s House of Delegates has voted to accept the recommendations of a report from the AMA Council on Science and Public Health, which address changes in lighting technologies and usage, recognition of the impact on sleep and sleep disorders, and further study of the possible link between light at night and cancer risk, obesity, and exacerbation of chronic diseases such as diabetes.

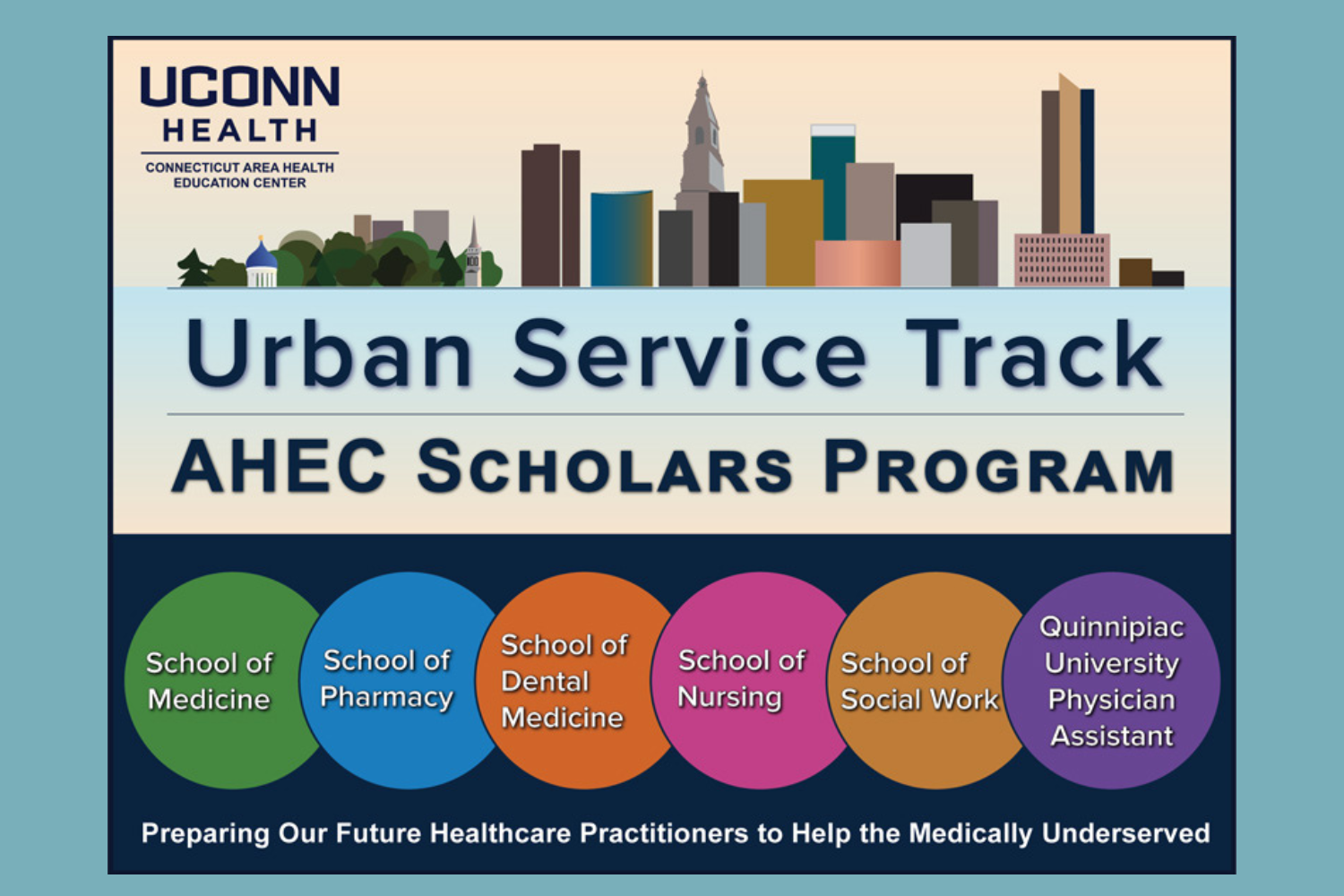

“It is a recognition by a major health body, the American Medical Association, that this is an emerging environmental issue that has a potentially large impact on the health of society,” says cancer epidemiologist Richard Stevens, professor in the UConn School of Medicine Department of Community Medicine and Health Care. “Based on an accumulation of evidence, this august body is now making the statement: ‘We take this seriously, and the public should take it seriously too.’”

The adoption of the council report’s recommendations by the AMA has the potential to influence federal grant money to study the health impact of artificial light at night.

Stevens was heavily involved in the writing of the report, titled “Light Pollution: Adverse Health Effects of Nighttime Lighting.” He is lead or co-author of nine of the research papers cited.

In scientific circles Stevens is widely credited with being the first to articulate the hypothesis that the increasing use of artificial light at night may be related to the high breast cancer risk in the industrialized world. His research in that topic goes back 25 years.

“There’s no question that this light at night changes our physiology in the short term,” Stevens says. “We know that artificial light disrupts circadian rhythms. We’re learning more and more about the specifics of what that means. The clearest evidence is about the hormone melatonin. We’re lowering it, we’re even suppressing it completely, depending on the amount of light.”

Melatonin has been shown to inhibit breast cancer in laboratory rats. Stevens is careful to say that the changes in human physiology from artificial light, circadian disruption and melatonin suppression have not been proven to cause breast cancer. Instead he offers a judicial analogy:

“It’s guilty in a civil trial, but no verdict in a criminal trial. A reasonable jury would say there is a preponderance of evidence, but it’s not beyond a reasonable doubt at this point.”

Five years ago, the cancer research arm of the World Health Organization declared night shift work as a “probable carcinogen.” Stevens was on the panel of scientists that made that determination.

Follow the UConn Health Center on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.