Pam Bedore approached the desk inside the Rare Books Room at the college library. A middle-aged woman looked up from her computer at the young graduate student.

“Can I help you?” the woman asked.

“I’m a new grad student here and I love rare books. I was just wondering if you could tell me about your collections.”

“Of course, Dear,” the woman said kindly. “Would you like to see the vault?”

The vault consisted of rows and rows of books, just like the stacks. And yet completely different. Bedore immediately felt the coolness of the space. Old books need a cool, dry environment to protect their fragile pages. The librarian turned switch after switch, flicking the lights to life as she motioned for Bedore to follow her down the corridor. They walked slowly between the storage shelves, as the librarian pointed out various collections of rare and valuable volumes, mostly leather-bound.

Suddenly, Bedore stopped.

“What are those?” she asked, gesturing toward a shelf lined with yellow-backed books. She looked down the aisle, and the paperbacks seemed to stretch on endlessly.

“Those are the dime novels,” the librarian said with the same reverence she had used in the Renaissance collection. “Rochester has one of the largest collections in the country. Over 10,000 volumes, although I’m afraid they aren’t all catalogued. No one is actually working with this collection at the moment.”

“Can I touch one?” Bedore asked.

“Of course,” said the librarian. “They were meant to be read.”

The first book she picked up had a handsome young detective on the cover catching a fainting lady. Bedore opened to the first page and was transported back to her childhood. In the small library of her hometown in Canada, she had read all of the children’s books, and that was where she had first followed the adventures of child detectives Nancy Drew, the Bobbsey Twins, and the Hardy Boys. She realized that from this day forward, her life would never be the same.

***

“The books I saw that day were about a thousand of the 1,465 Nick Carter dime novels,” says Pamela Bedore, now an assistant professor of English and writing coordinator at UConn’s Avery Point campus, who earned her Ph.D. at the University of Rochester. “That first year, while I was doing my doctoral coursework, I was very methodical. I’d go to the Rare Books Room and read dime novels for three hours each week.”

Reading those late 19th-century books, Bedore began to explore the dime store novels, discovering the core elements of detective fiction that can be found in the writings of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Mark Twain, William Faulkner, and in stories later developed for film, radio, and television. She traces those discoveries in a new book, Dime Novels and the Roots of American Detective Fiction, published in November by Palgrave/MacMillan as part of the Crime Files Series.

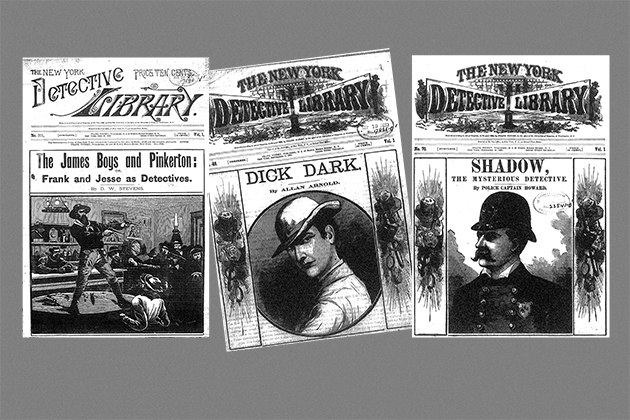

Detective stories began to become popularized with Nick Carter and Allan Pinkerton. Carter was a fictional character who first appeared in an 1886 series of popular books that were written by several different writers. Allan Pinkerton opened the nation’s first private detective agency and later wrote memoirs in the early 1900s based on some of his cases. He subsequently appeared as a character in various dime novels. The phrase dime novel is often used to describe various forms of late 19th- and early 20thth-century popular fiction.

“Maybe 30 people wrote the Carter dime novels, but three people wrote most of them,” says Bedore. “The author of Nick Carter was declared dead by The New York Times three times with these different authors.”

“Pinkerton is a very interesting character to look at,” she adds“He appears in numerous dime novels. Dashiell Hammett, who wrote The Maltese Falcon, was briefly a Pinkerton detective before becoming a writer.”

Armchair sleuths and hardboiled detectives

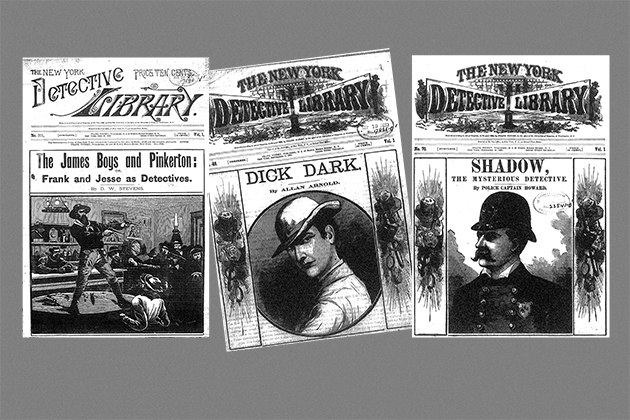

Bedore decided to focus her research on the New York Detective Library series of dime novels. She soon discovered that the stories and characters were quite different from each other, not the interchangeable tales described in the few earlier studies of dime novels.

“Everywhere I turned, the characterization of the dime novel followed the marketing – ‘This book is like every other book you’ve read. You’ll enjoy it,’” she says. “But I was seeing an armchair detective, a hardboiled detective, a procedural police detective. These are genres I’m familiar with. They shouldn’t be here in 1880.”

In her examination of the dime novels, she found the literary ancestors to armchair sleuths such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and Rex Stout’s Nero Wolf; hardboiled detectives like Hammett’s Sam Spade and Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe; and procedural police detectives in such books as Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct series and Joseph Wambaugh’s The Blue Knight.

Bedore says that despite the varying views about why detective fiction is popular – some readers like to solve the mystery, while others simply enjoy the telling of a good story; for those readers, the pleasure may be in following what she describes as the “contamination and containment” theme she found in dime novels that can still be found in modern detective fiction.

“We have this detective hero, but the more he or she interacts with the criminal element – tries to get into the head of the criminal, the chess game metaphor – the detective often realizes he or she is very similar to the criminal, sometimes becoming a murderer in the end and killing the criminal,” Bedore says. “I think that when we are following the detective, especially serial detectives, there is an understanding that they could always become corrupt. You know they’re not going to become corrupt, but the danger is always there.”

Deconstructing a popular formula

In addition to the class she teaches on American Detective Fiction, Bedore has taught several upper-level special topic classes such as Science Fiction, The Vampire in Literature and Culture, and Stephen King and Cultural Theory. She says compared to science fiction or horror novels, detective stories are “super formulaic.”

“It’s fascinating that despite that formulaic nature, detective fiction is so, so popular,” she says. “It seems straightforward to understand why sci-fi, which is constantly responding to anxieties about changing technology and science, is so popular. It’s harder to understand why detective fiction is so popular.”

Bedore notes that in teaching students about popular culture, she has the advantage of addressing a subject they are interested in. She tries to have them look at the subject with a more critical perspective, by posing questions about the underlying assumptions the genre may address and the questions they raise about topics like race, gender, class, or sexuality, but also about epistemology.

“I love the word epistemology. How do we construct knowledge, how do we agree on it, what is the truth?” she says. “It’s a question that’s at the center of detective fiction. With identity and epistemology as the central blocks, we start to look at popular culture and specific genres of popular literature. Once you’ve taken a couple of classes in pop lit, there is no beach reading anymore. It doesn’t exist, because beach reading is always going to be telling stories that matter to people for some reason. Once you start to think about why those stories matter – even when you’re reading the latest Twilight novel, you’re thinking, wait a minute – what is this saying about gender relations, or teen sexuality? Whatever the novel is, it’s always making you think.”

In her book Bedore suggests there are many new opportunities to explore dime novels and their lasting impact on detective fiction and other genres of literature. She is interested in continuing to explore the exploits of female detectives in the genre as well as the expanding diversity in detective heroes who are black, disabled, or elderly, as they have appeared over the years.

She also has another book project in development that would focus on three full-length dime novels from the New York Detective Library and would include notations and a variety of secondary materials aimed at demonstrating their influence on detective fiction as well as the American novel. This book, she adds, could serve as the centerpiece of advanced undergraduate or graduate courses in popular culture, detective fiction, or as introductory material for a curriculum in popular literature and culture in American literature or American Studies.