Research being done in UConn Health’s Center for Molecular Medicine is uncovering more evidence of differences between lesions found in the right side of the colon compared to the left side.

Those differences may help explain why colonoscopies are more effective in preventing left-sided cancers than right-sided. And while the implications are not fully known, understanding the earliest lesions that form in the right colon could hold the key to making colorectal cancer—a deadly yet largely preventable disease—more preventable and therefore, ultimately, less deadly.

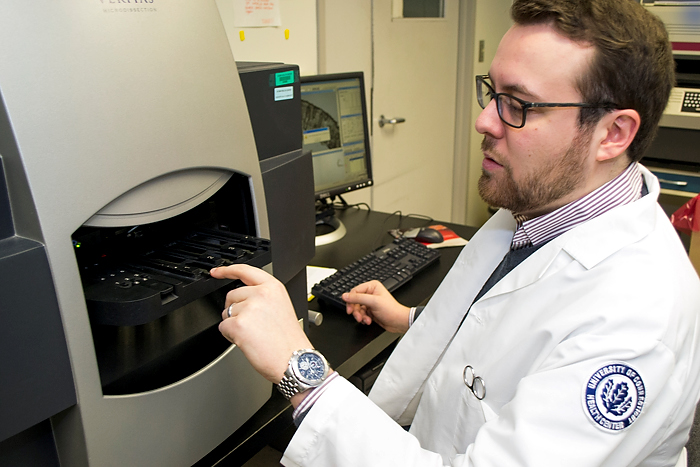

The study of these early lesions, known as aberrant crypt foci, or ACF, is taking place in the laboratory of Daniel Rosenberg, professor of medicine in UConn Health’s Department of Genetics and Developmental Biology. A key figure involved with that research is Ph.D. candidate David Drew.

“This work is central to my thesis,” Drew says. “It’s really the bulk of my dissertation.”

It also has drawn national interest. The American Association for Cancer Research chose Drew from a pool of more than 2,000 applicants as its AACR-GlaxoSmithKline Outstanding Clinical Scholar. The award recognizes “promising young cancer researchers who are the authors of outstanding proffered papers related to clinical research.” Drew is 27.

“David has tackled some enormously important issues in defining risk of colon cancer among the population,” Rosenberg says. “He has already published three papers and is about to submit a major epidemiological study of colon cancer risk in the Connecticut population, work that was a combined effort with Drs. [Thomas] Devers, [Richard] Stevens, [James] Grady and myself. There are some surprising and critically important observations that I think will have a major impact on how colon cancer prevention is implemented.”

Stevens, professor and cancer epidemiologist in the Department of Community Medicine and Health Care, calls Drew “a very capable young researcher with a good sense of epidemiology. He’s also an excellent basic scientist.”

Technology in the Rosenberg Lab enables researchers to visualize biopsies on a microscopic level, differentiating between cells from the lesions and cells from normal tissue. They also have developed a method of broad genetic screening on the samples, revealing mutations rarely associated with cancer.

“We’re trying to take those specimens back to our lab and understand the earliest genetic, epigenetic, and molecular changes that are happening in these lesions that may be contributing to your future risk of colon cancer,” Drew says.

Next week in San Diego, he presents his abstract, “Proximal human aberrant crypt foci as surrogate markers of colorectal cancer risk,” at the AACR’s annual meeting.

“We’re really interested in why those right-sided lesions specifically may be different than the left-sided lesions,” Drew says. “The work that I’m going to be presenting at AACR is really the first work that we did specifically looking at the right versus left, and what we’re learning is that these little tiny lesions on the right are different than the ones on the left.”

One of the questions is whether right colon lesions become cancerous more quickly, or whether they’re just not as detectable. Rosenberg Lab researchers hope analysis of these lesions at the molecular level can yield a better understanding. Sophisticated technology has enabled them to develop a broad genetic screen on tissue specimens, potentially revealing earlier clues about colon cancer risk.

“We’re trying to understand the first stages of initiation and understand what the earliest possible changes are that are occurring and contributing to colon cancer carcinogenesis,” Drew says.

“He will become a highly productive and successful cancer researcher and I have no doubt that he will head an academic research group in the near future,” Rosenberg says. “David’s translational focus has been instrumental in my securing several large extramural grants (NIH, DPH). He did a wonderful job in working together with several distinct disciplines to move the epidemiology paper forward.”

Later this year Drew expects to complete his thesis at the UConn Health Graduate School and leave with a Ph.D. in biomedical science. He and his wife, Katelyn Dannheim, live in West Hartford, but are soon likely to move to the Boston area; Dannheim is graduating from the UConn School of Medicine next month and will begin residency training in pathology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Drew graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., with a Bachelor of Science in biochemistry/biophysics, and stayed at RPI for graduate school. Within the first year, his principal investigator took a job at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, leaving him with the choices of following her to Vanderbilt, staying at RPI in another lab, or starting over somewhere else. The fact that his then-girlfriend was a medical student led him to UConn, and his interest in genetics and translational research led him to Rosenberg, who calls him “one of the finest students I have ever trained.”

“I’ve been given a great opportunity here,” Drew says. “I consider myself very lucky. Not everybody gets work that I get, that is so translational and conducive to publishing.

“You never hear about the failures in science very often, unless they’re catastrophic. We fail a lot, but that’s part of science. But every time something doesn’t work, we learn something from it. And that’s a great skill to have, for life, for professionalism and for research.”

Follow UConn Health on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.