An environmental engineer who earned his Ph.D. at UConn in 1999 has been named a 2015 MacArthur Fellow.

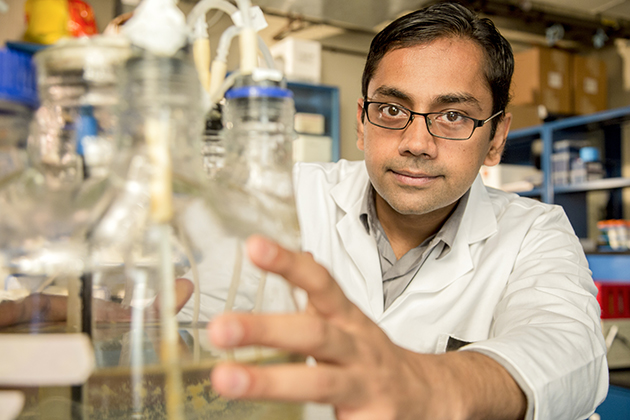

Kartik Chandran ’99 Ph.D. integrates microbial ecology, molecular biology, and engineering to transform wastewater from a troublesome pollutant to a valuable resource. He is one of 24 individuals recognized this year with a so-called MacArthur ‘genius grant.’

The MacArthur Fellows Program awards unrestricted fellowships to talented individuals who have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits and a marked capacity for self-direction.

My years at UConn created the foundation for a lot of work that I do now. — Kartik Chandran ’99 Ph.D., MacArthur Fellow

Now at Columbia University, Chandran aims to use wastewater to produce useful resources such as fertilizers, chemicals, and energy sources, as well as clean water, in a way that takes into account current climate, energy, and nutrient challenges.

“As a society, we are faced with multiple challenges, including lack of clean water, lack of energy, food security,” says Chandran in a video on the MacArthur Foundation website, “so our philosophy, our vision is to address these multiple challenges in conjunction and not in isolation.”

Traditional facilities for biologically treating wastewater use decades-old technology that requires vast amounts of energy and resources, releases harmful gases into the atmosphere, and leaves behind material that must be discarded.

In an article in the School of Engineering’s newsletter Momentum in 2012, Chandran credited his Ph.D. advisor, former UConn environmental engineering professor Barth Smets, with introducing him to the need for processes that reduce and remove excess nitrogen from the environment.

“One of the first projects that I worked on, starting during the fall of 1997, was on improvements to the design and operation of a biological nitrogen removal plant in Connecticut,” he said, “and this really set the tone for my research and technology development that I do currently.

“My years at UConn created the foundation for a lot of work that I do now,” Chandran added, “and the concepts, ideologies, and work ethic that I learnt while at UConn permeate my activities even today.”

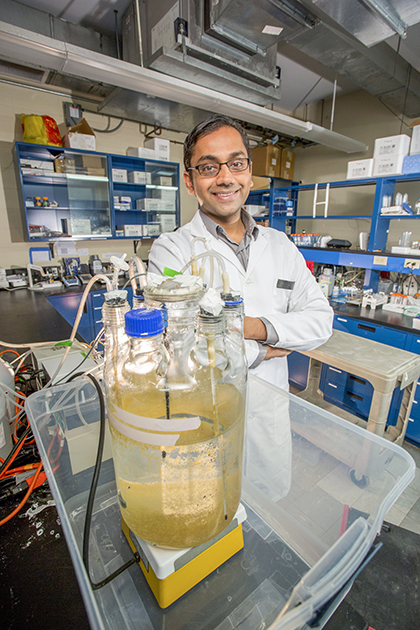

The key insight of Chandran’s research and its applications is that certain combinations of mixed microbial communities, similar to those that occur naturally, can be used to mitigate the harmful environmental impacts of wastewater and extract useful products.

For example, he has determined an optimal combination of microbes (and associated wastewater treatment technologies) to remove nitrogen from waste while minimizing the release of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas. This approach also involves reduced chemical and energy inputs relative to traditional treatments and has the added benefit of preventing algal blooms downstream by maximizing nitrogen removal.

“If you start to think of [waste streams] as enriched streams,” says Chandran in the MacArthur Foundation video, “these now contain resources that we could extract and recover and use.”

More recently, using ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, Chandran has enabled the transformation of bio-generated methane gas into methanol, a chemical that is both easily transported and widely useful in industry, including the wastewater industry.

Chandran tailors his solutions to local circumstances. One example of his field work is in rural Ghana, where he has re-engineered source-separation toilets to not only provide sanitation but also recover nutrients for agricultural use. In Kumasi, Ghana, he is testing the large-scale conversion of sludge into biofuel, while also providing new training opportunities for local engineers and managers.

Chandran says he would like to use the resources afforded by the MacArthur Foundation to apply the innovations he is developing to address global needs.

After earning his doctorate at UConn in 1999, Chandran spent a further two years at UConn as a postdoctoral research fellow. He went on to work as a senior technical specialist (2001-2004) with the private engineering firm Metcalf and Eddy of New York Inc., and a research associate (2004-2005) at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, and is now an associate professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Engineering at Columbia University. His work has been published in such journals as PLoS ONE, Environmental Microbiology, Environmental Science & Technology, and Biotechnology and Bioengineering, among others.