Mainline Protestant churches, despite decades of advocacy for racial justice in society, are the least likely among Christian groups to respond to email inquiries about membership from people who have non-white sounding names, according to a paper published this fall by University of Connecticut researchers.

By contrast, the study found, evangelical Protestants, who typically belong to politically conservative denominations wary of political goals associated with secular liberalism, show almost no variation when it comes to responding to potential new congregants, regardless of race. The study was published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion.

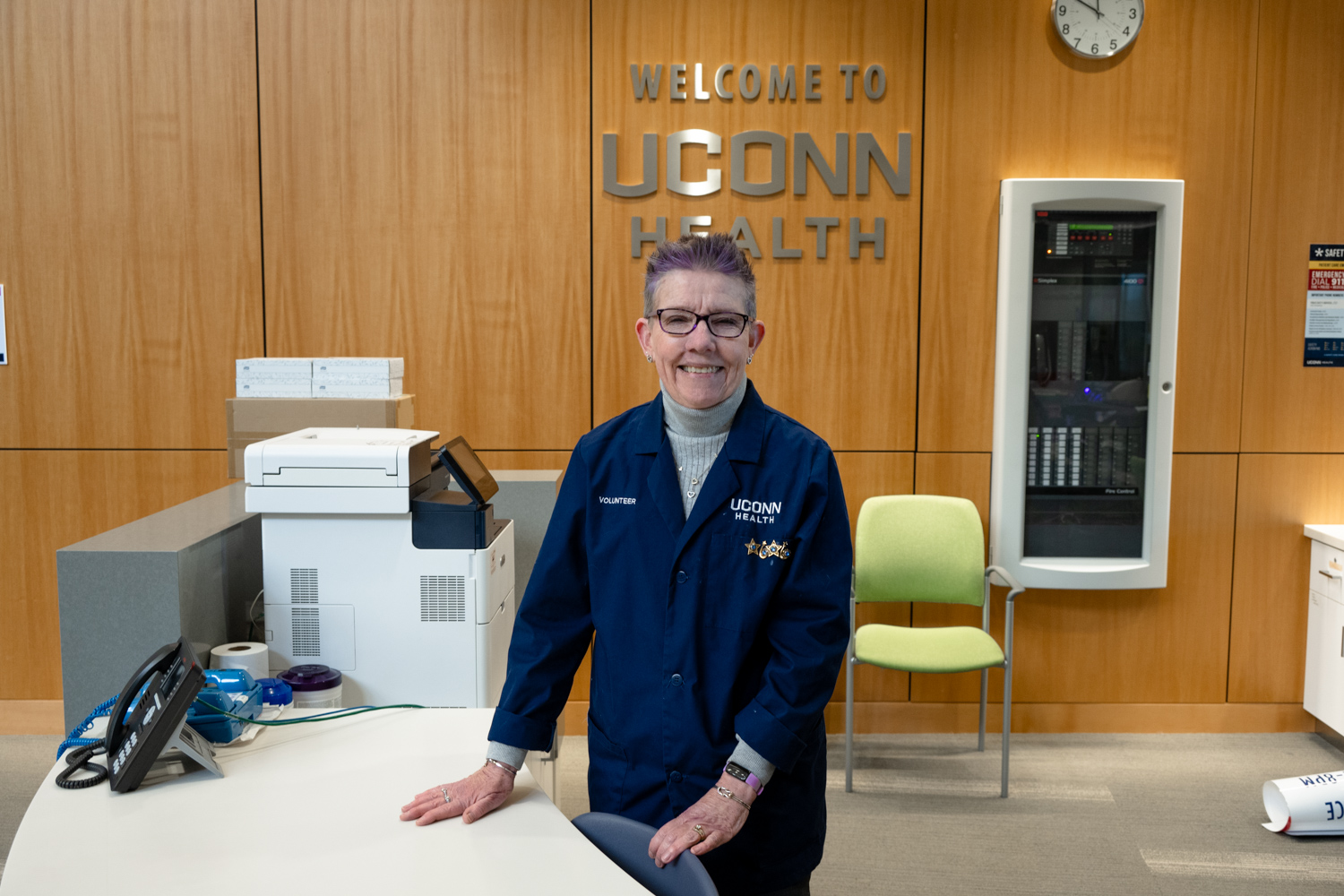

The principal authors of the study, UConn sociology professors Michael Wallace and Bradley Wright, say this type of research provides better insight into attitudes about race as they’re actually lived, rather than more old-fashioned question-and-answer surveys.

“You’re reaching people in an unguarded moment this way,” Wright says, “which gives us an opportunity to see how people actually behave, as opposed to what they might tell a pollster on the phone.”

According to the research, 67.1 percent of whites who sent e-mails to Protestant churches received at least one response, compared to 57.5 percent of blacks, 59.7 percent of Hispanics, and 48.9 percent of Asians.

By contrast, 59.1 percent of whites who wrote to evangelical Protestant churches received responses, compared to 59.0 percent of blacks, 57.7 percent of Hispanics, and 55.9 percent of Asians. Among Catholics, the numbers were 70.8 percent of whites receiving responses, 66.2 percent of blacks, 60.0 percent of Hispanics, and 64.6 percent of Asians.

“A lot of this has to do with where people live, first and foremost,” Wallace says. “One of the reasons people affiliate with churches or any other group is because they like being around other people who are like them.”

The study was designed by creating a nationally representative sample of 3,113 churches from the three largest Christian traditions in the U.S. The researchers then crafted a brief email inquiring about joining a particular church, and randomly assigned names typically associated with whites, blacks, Hispanics, and Asians to the emails.

They found that not only did emails from white people receive the most responses, but that responses to whites tended to be longer in word count and more effusive, by several quality measurements, than responses to non-whites.

The results weren’t entirely surprising to Wallace and Wright, given the segregated nature of American Christianity. Despite the Biblical admonition to “go therefore and make disciples of all nations,” about 86 percent of American Christian congregations draw at least 80 percent of their members from a single racial group.

But what did surprise Wallace and Wright was the disconnect between the institutional commitments of mainline denominations and the day-to-day behavior of the churches themselves.

“Mainline Protestants will focus on social change rather than individual change – what’s known as ‘structural justice,’” Wallace says. “Evangelical Protestants, on the other hand, tend to be more focused on how individuals behave, or ‘interactional justice’.”

Wallace and Wright say the study has implications beyond individual churches’ ability to live up to the principles of their faiths. Religious segregation both reinforces racial inequality throughout society, and redirects social resources, since churches play such a vital role as hubs for networking, civic participation, and charitable support.

“This is something that Christians, and non-Christian Americans, should be concerned about,” Wright says. “It’s one thing to express a commitment to racial harmony, but it’s another thing entirely to live up to that commitment.”