As the first official voting for the 2016 Presidential Election nears, with the Iowa caucuses on Feb. 1 and the New Hampshire primary on Feb. 9, a new book by a UConn political scientist examines how American politics have been changed by the symbolic empowerment of historic first-time candidates.

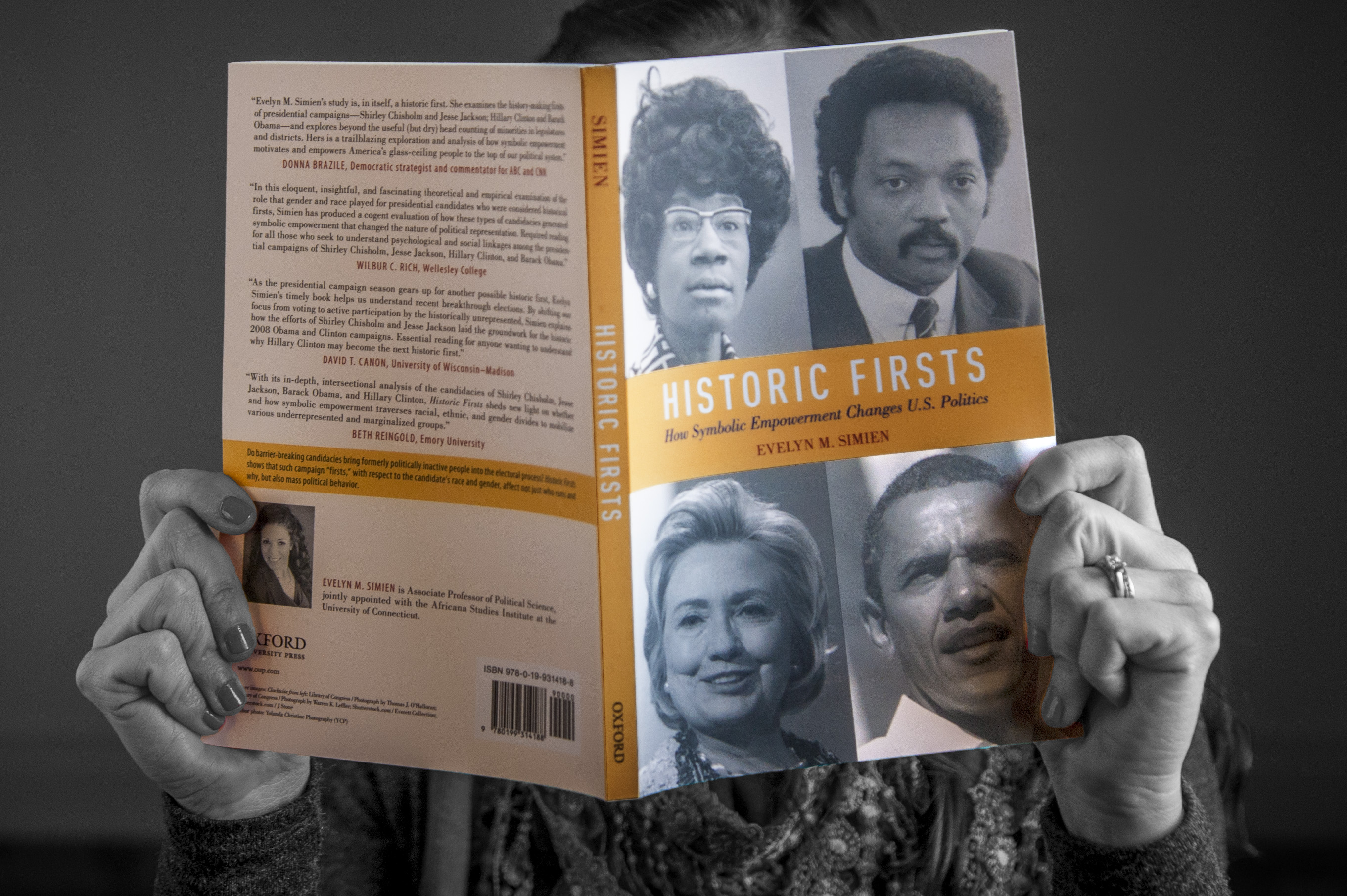

Historic Firsts: How Symbolic Empowerment Changes U.S. Politics (Oxford University Press 2015) by Evelyn M. Simien, associate professor of political science in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the Africana Studies Institute, traces the influence of the presidential campaigns of U.S. Rep. Shirley Chisholm and the Rev. Jesse Jackson on the 2008 Democratic primary battle between U.S. Sens. Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama.

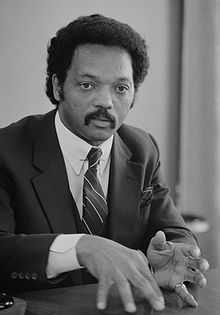

In 1972, Chisholm – the first African-American woman elected to Congress – became the first African-American woman to run for president. In 1984, Jackson, a longtime civil rights leader, became the first African-American man to launch a presidential campaign, which he followed in 1988 with a national campaign. Simien says the Chisholm and Jackson Democratic primary campaigns set the stage for the mobilizing effect decades later of the Clinton and Obama campaigns on attracting first-time volunteers, donors, and others who felt empowered to become involved in the 2008 election after seeing candidates who look like the voters.

“Symbolic empowerment has to do with a moment when a historic first emerges onto the political scene, and their historic candidacy elicits a sense of hope, good feeling, and pride that then stokes the desire to actively participate in the campaign when previously that had not been the case,” says Simien. “Not only do you register to vote, but you donate money, attend a rally, talk about the campaign, and follow the debate. In that sense someone who previously had been disengaged goes from zero to 100 almost overnight over the historic nature of this candidacy.”

Chisholm and Jackson were not viewed as likely to win their party nomination, but received attention because … [they] were able to give voice to issues of importance to communities of color.

Simien studied a wide range of scholarly sources – from voter turnout reports and national telephone surveys to campaign speeches and political advertising – to analyze both how and why individuals participated in the campaigns. She initially began to study the Clinton and Obama campaigns to write a scholarly paper for the Northeast Political Science Association. After being invited to provide perspective on the Chisholm presidential run for a Women’s History Month presentation at the Hartford Public Library, she determined there were links between the three historic candidates and felt that Jackson’s campaign also was part of the grouping.

“For a lot of people, it was quite a phenomenon to see or witness the mobilizing effect of Obama, where droves of people are making phones calls donating money, going to rallies, not once but twice during the course of the campaign,” says Simien. “It was true of people who were supporters of Chisholm in ’72 and Jackson in ’84 and ’88. One common thread is the mobilizing effect they had particularly on African-American female voters, who have come to represent the new Democratic voter. I don’t think that is spotlighted enough.”

Simien says that both Chisholm and Jackson were not viewed as likely to win their party nomination, but received attention because of the historic nature of their candidacies and were able to give voice to issues of importance to communities of color at the national nominating convention, a legacy of the voting rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer. During the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, N.J., that nominated Lyndon B. Johnson for president, Hamer was a leader of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegation that challenged the all-white Mississippi delegation before the convention’s Credentials Committee.

In the 2008 primary election, Simien says, Clinton’s candidacy showed that group consciousness among women does not have the same mobilizing effect on white women that it does on women of color. African-American women have a dual identity as both black and female, she notes, and when they had to choose between the two Democratic candidates, aligned with Obama.

“Gender, or feminist consciousness, does not have the same effect on women voters,” she says, noting that there are white female voters who will vote Republican despite the chance to vote for a Democratic candidate of their own sex, as was the case in 1984 when Geraldine Ferraro was the Democratic vice president nominee. “Group consciousness does not serve the same catalytic effect. It has a differential effect on respective women.”

In looking at the upcoming 2016 presidential contest, Simien says the potential nomination of a Hispanic man by the Republicans – Sens. Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz – would present Latina voters with a similar decision on their choice of a candidate if Clinton wins the Democratic nomination.

Simien says Hispanic women have not faced the “cross-pressure” that African-American women experienced in 2008. And the choice for Latinas, who generally identify as Democrats, could be between a more conservative Republican candidate of their ethnicity and a woman of their own sex with more liberal views.

“The Latino population is not a monolithic group,” Simien adds. “There are Cubans who identify as Republicans and will vote according to party line. It’s an empirical question that we as political scientists should be looking at.”

She notes that the 2016 election is an opportunity to gather more detailed voter data that was not available in previous most recent presidential elections, particularly data on Latino and immigrant voters.

“When they conduct these polls, they have to do oversamples of the Latino population and disaggregate that community; in other words, break it down,” she says. “It will be important to look at Cuban Americans, and look at them compared with other Latino populations – not only by ethnicity, but by majority.

Simien says this year’s election could help answer a question she hopes to examine as the next step in her study of historic firsts: “Will gender trump ethnicity?”