Medicinal chemist Marcy Balunas spends a lot of her time isolating natural compounds from marine life, hoping to find new drugs that may one day lead to better treatments for a particular pathogen or disease.

The potential rewards are great. But the odds are long and the work, at times, can seem like a litany of dead ends.

So Balunas was understandably excited when she learned that a UConn research group led by molecular and cell biologist Spencer Nyholm had identified bacteria that appear to play a role in protecting the Hawaiian bobtail squid’s eggs from fungi and other microorganisms before they hatch.

Seeing the squid has already pre-selected the bacteria as effective antifungal agents to meet its evolutionary needs, it was one heck of a lead.

Now, the two are teaming up to explore the bacteria’s unique characteristics further. They recently received a $680,000 National Science Foundation grant that will allow Balunas – an assistant professor in the School of Pharmacy – to take a closer look at the chemistry behind the bacteria’s role in inhibiting fungi and other microorganisms, to see if potential antibiotic or antifungal drug compounds lie in the offing.

Initial tests look promising.

“In our initial extractions from the bobtail squid bacteria, we have seen a substantial number of samples that are very potent,” says Balunas. “Typically, if we screen soils or soil fungi for antibacterials, we might have a hit rate of 2-5 percent. With these squid, the hit rate is more in the range of 20-30 percent.”

Once the new compounds are isolated, Balunas will test them against known human pathogens such as MRSA and Candida albicans, a yeast-based fungus that causes oral and genital infections in humans. Both pathogens can pose serious health threats to individuals whose immune systems are compromised and both are notoriously resistant to certain antibiotics.

The funding will also allow Nyholm – an associate professor of molecular and cell biology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences – to characterize the bacteria’s gene expression in order to get a better understanding of its biological function and symbiotic relationship with its host, including whether the bacteria may have a role in the development of the squid’s accessory nidamental gland (ANG). Scientists have long been puzzled by the tiny gland’s function and purpose.

While Balunas drills down into the bacteria’s chemistry, Nyholm is focusing on the broader view.

“What I want to understand is how these beneficial associations are established and maintained,” he says. “How does the squid’s innate immune system differentiate between beneficial bacteria and harmful bacteria?”

This isn’t the first instance where scientists have noticed the Hawaiian bobtail squid using beneficial bacteria to aid in its survival. Researchers like Nyholm study the squid because of the unique symbiotic relationship it has with a species of bioluminescent bacteria living in a specialized “light organ” attached to its ink sac. The tiny squid uses the bacteria to light up its abdomen, matching the luminosity of moonlight in order to camouflage itself from predators while hunting at night. In return for the protection, the squid provides the bacteria with a safe place to live and grow.

Beneficial relationships in which one organism relies on another to survive – such as bacteria protecting a species’ eggs – is known as defensive symbiosis and is a rapidly growing field in science, says Nyholm.

“The antifungal application is another type of defensive response,” he says. “The squid may be using the bacteria to defend their eggs, almost like a different arm of their immune system. There is a lot of research going on right now into these kinds of chemical defensive symbioses, and there are a lot of examples in nature where organisms are doing this.”

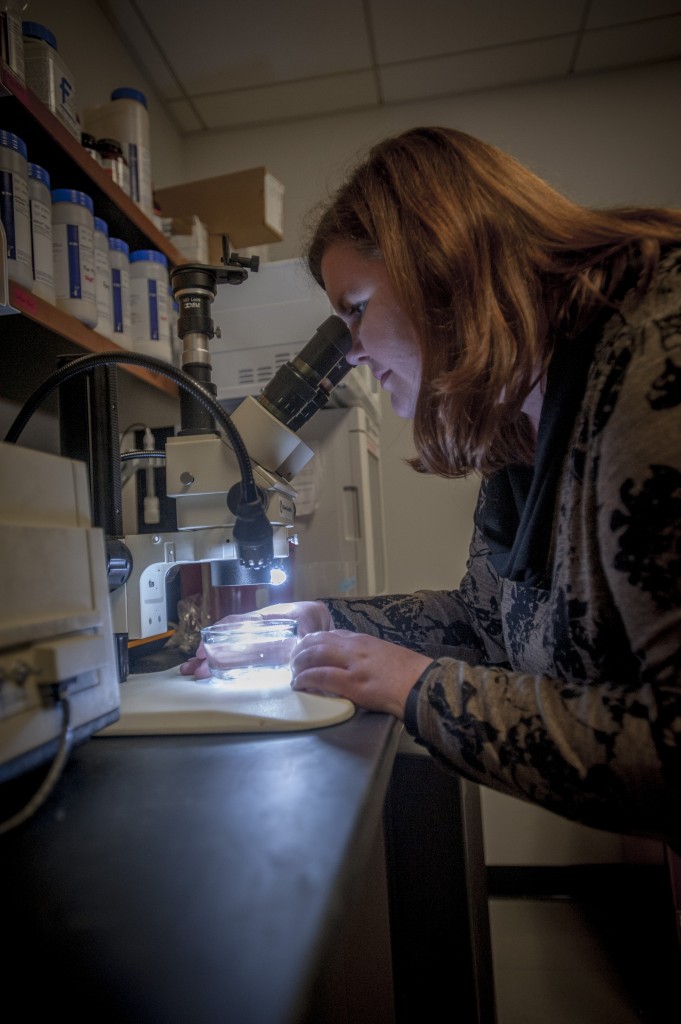

While scientists suspected some form of beneficial bacteria may be involved in protecting the squid’s eggs from the elements while they mature inside a jelly-like sac, it wasn’t until a member of Nyholm’s research group tested the theory that it was confirmed. Graduate student Allison Kerwin exposed squid eggs to antibiotics and observed how they quickly became overgrown with fungi once the bacteria were neutralized. Other students – Andrea Suria in the Nyholm lab and Samantha Gromek and Anne Sung in the Balunas lab – are now following up with the genetics and chemistry of these bacteria to help understand how they may be producing antifungal compounds.

“We know these bacteria belong to a class known as Alphaproteobacteria, and within that class is a group called Roseobactors,” says Nyholm. “Roseobactors have been linked to some interesting anti-algal and antibacterial compounds, but we may be the first to implicate them in antifungals and that’s kind of exciting.”

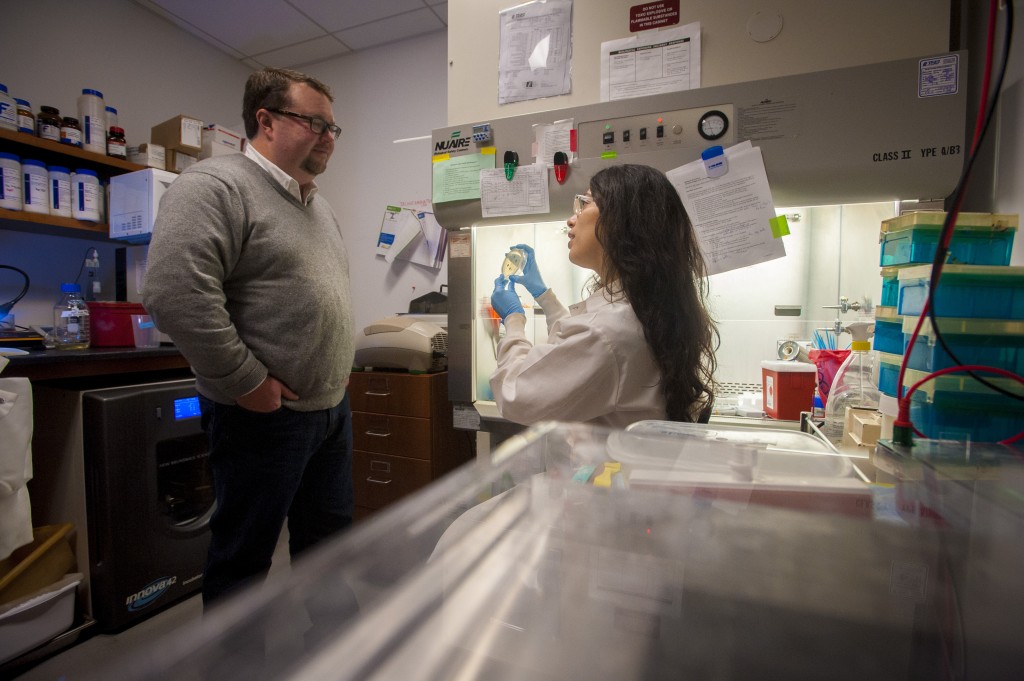

Balunas and Nyholm say their collaboration has been key to advancing the science. While Nyholm’s lab can isolate the gland bacteria and culture them, Balunas can then take the testing to the next level by extracting specific chemical compounds to probe the bacteria’s properties further.

“My expertise is on the symbiosis side, the host, the immune system, and the bacteria,” says Nyholm, “but I don’t know how to extract the important chemical compounds that might generate the actual activity. That’s where Marcy’s expertise kicks in.”

Says Balunas: “Most people in my field are doing random collections and don’t have such a strong microbiology collaborator. Spencer’s ability to probe the microbiology and genetics couples very nicely with our research into the chemistry and drug discovery.”