When white supremacists and neo-Nazis rallied in defense of a statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia in August, they got one thing right, according to Manisha Sinha: They understood the significance of Confederate monuments.

There are always antecedents to what we’re seeing now if we look back into our history. — Manisha Sinha

“Not only was the Confederacy founded on the idea of racial inequality, but monuments to it arose at moments in American history when southerners sought to defend white supremacy,” the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair of American History wrote in August in the New York Daily News.

In this case, that moment was after the Civil War and the fall of the Reconstruction, after Federal troops had vacated the defeated South, and “disenfranchisement, segregation, and racial violence reared up on a massive scale,” she notes.

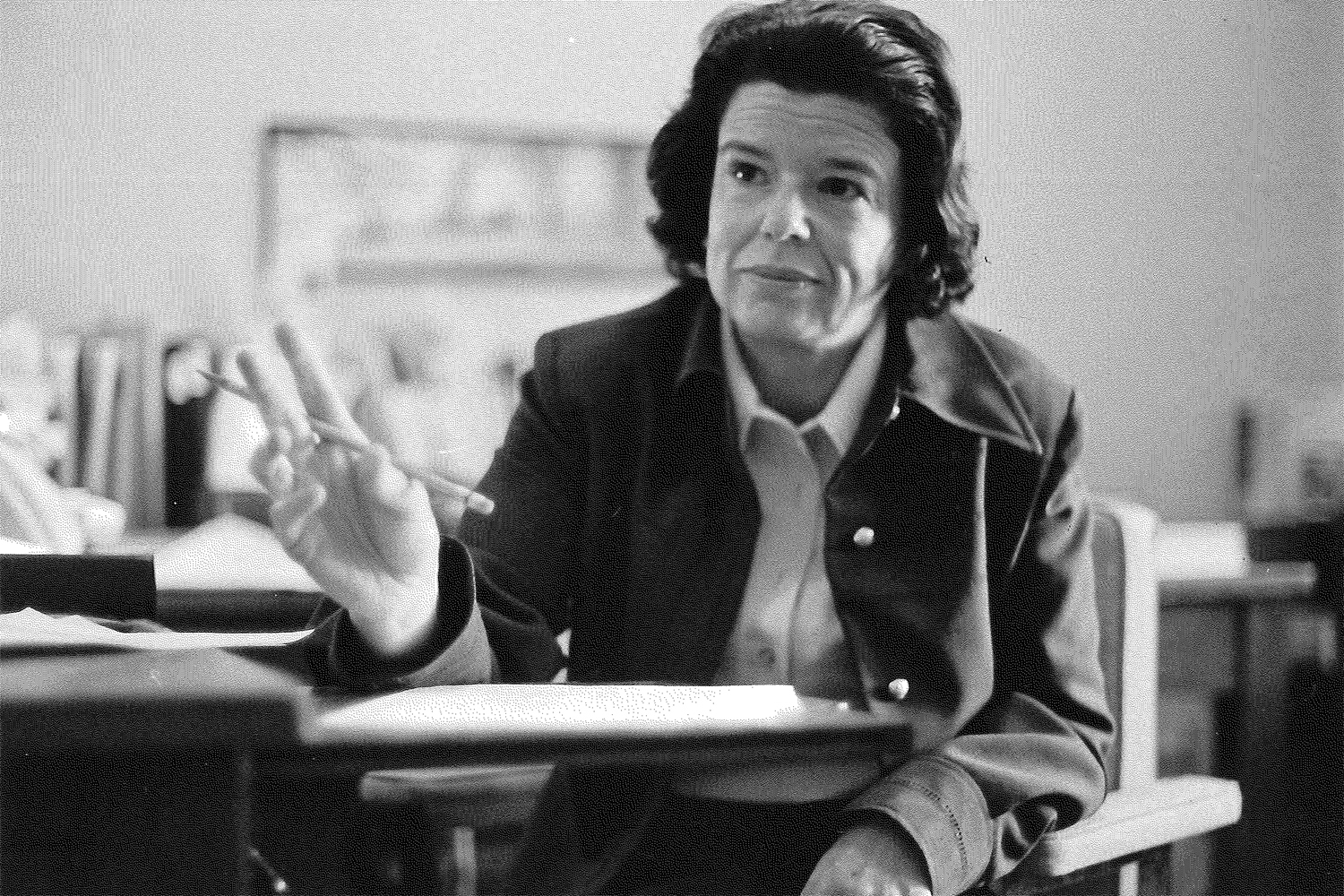

Sinha’s historical work sharply parallels current politics, including the success of movements that placed Barack Obama in power, and the current resurgence of conservative ideals. Now, she brings her unique perspective to UConn as the new James L. and Shirley A. Draper Endowed Professor of History.

“You can really see how American democracy does not progress in one linear path,” she says. “It moves in fits and starts, and you can lose things that you have won very quickly.”

The Slave’s Cause

Born and educated at the undergraduate level in India, Sinha grew interested in the American civil rights movement because Martin Luther King Jr. espoused many of Gandhi’s principles of nonviolent resistance. She came to the U.S. at age 21 to attend graduate school in history at Stony Brook University and Columbia University, where her dissertation on slaveholders and slaveholding was nominated for the competitive Bancroft Prize. Much of her dissertation is referenced in her first book, The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina (The University of North Carolina Press 1994). After that, she switched gears.

“I wanted to write a book about people I actually liked,” she laughs.

The Slave’s Cause focuses on the importance of organized slave resistance to the abolition movement. It has racked up a list of national awards, including, most notably, being long-listed for the 2016 National Book Award for Nonfiction, and being a finalist for the Frederick Douglass Book Prize, jointly sponsored by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at the MacMillan Center at Yale University.

Her book traces some of the earliest anti-slavery organizations, such as slaves in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire who were petitioning for their freedom long before the Civil war – as early as the Revolutionary Era. Groups called the Anti-Slavery Committee and the Sons of Africa were crucial to the movement by creating their own program not only of abolition, but of desegregation and racial equality. These early black abolitionists influenced white abolitionist speakers and publishers like William Lloyd Garrison, who adopted their rhetoric and program.

“These groups were already imagining the interracial democracy we live in today,” says Sinha.

“It’s a tendency when we write U.S. history not to incorporate other histories,” she notes. “You have African-American history, you have women’s history, you have labor history, you have ethnic and immigrant history … and somehow you never end up incorporating these insights into rewriting U.S. history itself.”

“It’s a tendency when we write U.S. history not to incorporate other histories,” she notes. “You have African-American history, you have women’s history, you have labor history, you have ethnic and immigrant history … and somehow you never end up incorporating these insights into rewriting U.S. history itself.”

Many historians have concluded that most abolitionists were progressive about slavery but conservative about other issues. Sinha rebuts this argument, saying that abolitionists tended to be “eclectic and diverse,” and to intersect with other human rights groups, like the women’s movement. She calls women the “footsoldiers of the abolitionist movement,” noting that they did much of the canvassing door-to-door and keeping abolitionist lecturers and publications afloat.

“They out-signed men in abolitionist petitions nearly 2 to 1,” Sinha says. “Most of the early feminists were abolitionists. Even though they were not considered citizens, they were doing really important work.”

An Incomplete Reconstruction

Sinha wrote The Slave’s Cause during the Obama administration, during which she saw many modern parallels with her book. After slavery was abolished and the Civil War ended, pathbreaking civil rights laws were passed, and Reconstruction held the promise of an era of progressive thinking. The tragedy, says Sinha, is that it all fell apart.

“You have a wonderful period that was all overthrown, and there was a regression into massive racial violence,” she says. “This is precisely when the South erected all these monuments to the Confederacy, to commemorate their lost cause.

American democracy … moves in fits and starts, and you can lose things that you have won very quickly. — Manisha Sinha

“It’s a time where the Southern way becomes the national way. It fits in exactly with what we’re experiencing now, with the Trump presidency – there’s an immense racial backlash. It’s not something that belongs to the past – it’s why the Civil War and its history is so pertinent today.”

Sinha’s upcoming book project, for which she received her second career National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship in 2015, will focus on the Reconstruction, and how the country pieced itself together after the Civil War.

“We think when slavery was ended, that’s all abolitionists wanted,” she says. “But they were really fighting to redefine American democracy as an interracial democracy. And there’s a lot of that still going on right now.”

Recasting History

As the new Draper Chair in American History, Sinha will take on the role of connecting American history to the past in public workshops.

“There are always antecedents to what we’re seeing now if we look back into our history,” she says.

The first Draper Workshop on Nov. 6 will discuss the issue of Confederate monuments and what they represent as part of American history. Called “Recasting the Confederacy,” the forum will include several public historians who have spoken out in the news media about monuments and their meaning.

She hopes this and other future Draper events will keep the University community and the public talking about how today’s political events have real and useful connections to our past.

“The notion that somehow history will progress, that we’ll get over this dark period – that never happens on its own,” she says. Unless ordinary American citizens, men and women, white and black, take it on themselves to move the pendulum of history in the right direction, it’s not going to move on its own.”