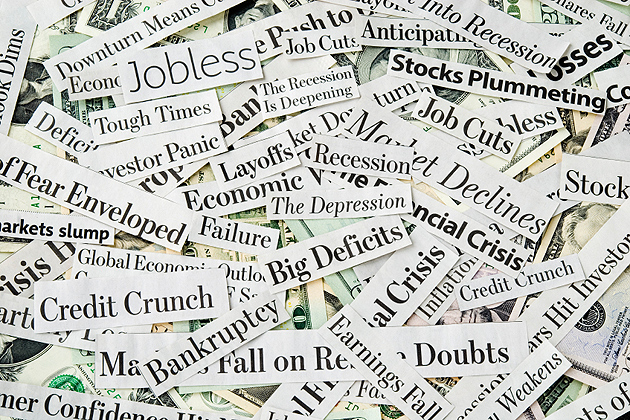

In recent years, the American public has grown increasingly skeptical of the existence of man-made climate change. Although pundits and scholars have suggested several reasons for this trend, a new study shows that the recent Great Recession has been a major factor.

Lyle Scruggs, associate professor of political science in UConn’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, suggests that this shift in opinion is related primarily to the public’s concern about the economy.

“That the economy impacts the way people prioritize the problem of climate change is uncontroversial,” says Scruggs. “What is more puzzling is why support for basic climate science has declined dramatically during this period.

“Many people believe that part of the solution to climate change is suppression of economic activity,” which is an unpopular viewpoint when the economy is bad, Scruggs continues. “So it’s easier for people to disbelieve in climate change, than to accept that it is real but that little should be done about it right now.”

Scruggs and UConn political science graduate student Salil Benegal published their findings online in the journal Global Environmental Change on Feb. 24. An abstract is available here.

The study relies primarily on information drawn from a number of national and international public opinion surveys dating to the late 1980s.

The researchers found significant drops in public climate change beliefs in the late 2000s: for example, the Gallup 2008 poll reported that between 60 and 65 percent of people agreed with statements of opinion that global warming is imminent, it is not exaggerated, and the theory is agreed upon by scientists. By 2010, those numbers had dropped to about 50 percent.

The authors also found a strong relationship between jobs and people’s prioritization of climate change. When the unemployment rate was 4.5 percent, an average 60 percent of people surveyed said that climate change had already begun happening. But when the jobless rate reached 10 percent, that number dropped to about 50 percent.

The paper also evaluated three other explanations for the crisis in public confidence: political partisanship, negative media coverage, and short- term weather conditions.

“We think that this is the first study to consider the economy and these explanations at the same time, says Scruggs.”

Of these, the authors found that faith in climate change dropped across political parties, among Republicans, Democrats, and independents. They also found that that the “Climategate” email hacking controversy and reported errors in the 2010 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, which both occurred after public faith in climate change began to drop, were not factors.

The authors did find that if people had experienced a recent change in short-term weather, they were more likely to believe that climate is changing over the long-term. But when the study controlled for these effects, the economy mattered more than the weather, says Scruggs.

The authors also marshaled international evidence showing that European opinion points in the same direction.

“There is probably a stronger overall ‘pro-climate’ ethos in Europe,” says Scruggs. “Still, even in Europe, countries experiencing more severe national recessions saw larger declines in beliefs that global warming was occurring.”

The researchers speculate that cognitive dissonance, which arises when people experience conflicting thoughts and behaviors, could explain this pattern. Most people view economic growth and environmental protection to be in conflict, so admitting that climate change is real but should be ignored in favor of economic growth leads to an internal philosophical clash.

“Psychologically, people have to evaluate economic imperatives in the recession, and that can create conflicting concerns,” Scruggs says.

When confronted with a desire to boost the economy, he continues, people seem to convince themselves that climate change might not really be happening.

Now that the economy is beginning to bounce back and the unemployment rate is shrinking, Scruggs says it makes sense that belief in global warming has begin to rebound.

“We would expect such a rebound to continue as the economy improves,” he says. “You wouldn’t make that prediction if you think something else, like political rhetoric, is the issue.”