As Russia moved to begin annexing Ukraine’s Crimea region earlier this month, history professor Frank Costigliola assigned his students three readings for a discussion of the recent events.

The assignment, part of his “Rise of U.S. Global Power” class, included commentaries by Jack Matlock Jr., who was President Ronald Reagan’s ambassador to the Soviet Union, and political columnist Charles Krauthammer, who coined the phrase “Reagan Doctrine” to describe Reagan’s opposition to the global influence of the Soviets during the end of the Cold War era.

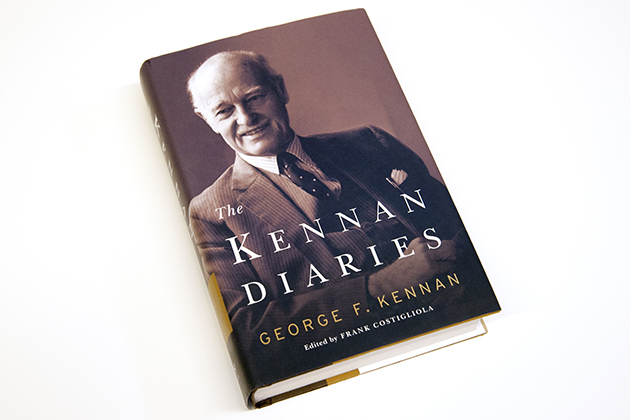

The third reading was Costigliola’s own commentary from The New York Times, in which he provided insight about the history of U.S. relations with the Soviet Union through the eyes of longtime diplomat George F. Kennan, a former ambassador to Moscow and Yugoslavia who was a key figure in establishing the containment policy toward the Soviets during the Cold War. Costigliola edited the recently published book “The Kennan Diaries” (Norton 2014), which is praised by Kennan’s biographer, John Lewis Gaddis, and two former Secretaries of State, Henry A. Kissinger and George P. Schultz.

Costigliola described the classroom discussion as “a golden moment,” a rare confluence of current events intersecting with history that allowed his students to gain perspectives far beyond their classroom text.

“It was helpful and enlightening for my students for me to bring the personal element of how Kennan was recommending one thing in 1946-47 and taking a different direction in later years,” Costigliola says.

A prolific writer and authority on the Cold War era, Costigliola served as a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in 2009, when access to Kennan’s papers was expanded. After leaving the diplomatic corps, Kennan spent 50 years at Princeton, his alma mater, writing about foreign policy and diplomatic history. He died in 2005 at the age of 101.

During his fellowship at Princeton, Costigliola became fascinated by the material contained in the 8,100 pages of handwritten diaries that began when the diplomat was a child.

“I’ve never edited something like that before. The biggest challenge was getting to within a respectable, feasible length,” says the historian. “Kennan wrote beautifully, almost like calligraphy. There’s a lot of words on each page. I went through it four times, each time cutting it down more and more. I wanted all the aspects of his personality to come through: the political stuff, the elegance of his writing, and representative sections of the various periods of his life.”

The ‘Long Telegram’

Kennan was on assignment to Moscow early in the post-World War II era of U.S.-Soviet relations when he sent a 5,540-word cable to his superiors in Washington outlining his view that the Soviets were seeking to expand their influence in the world and that the effort should be contained. The 1946 dispatch, known as “The Long Telegram,” and a subsequent article in Foreign Affairs magazine titled “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” written in 1947 under the alias “X,” became the foundation of America’s Cold War policy toward the Soviet Union.

Costigliola says Kennan later felt the documents were “an albatross around his neck,” and he became critical of American foreign policy, arguing that containment could be achieved via a more open dialogue with the Soviets.

“Kennan was arguing first within the government and then outside the government for a re-engagement with the Soviet Union, for removing some of the blocks for containment, and attempting diplomacy again and trying to understand issues from the Soviet point of view,” Costigliola says. “… Kennan was arguing again and again in subsequent years that there are two sides to every issue.”

A man of discretion

Costigliola says that in editing the thousands of pages of the diaries he focused primarily on the political insights Kennan recorded, and was surprised by the absence of his views on many key historic moments, including the German invasion of Poland in 1939 and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. The diplomat was also silent when advising George C. Marshall, who served as Secretary of State during the Truman Administration.

“When he can’t advise the Secretary of State, he writes in the diary,” Costigliola notes. “In 1947, he had the ear of the Secretary of State. He loved to be at the center of things. In the rush of being a policy maker and planner, he doesn’t need the diary. The other thing was that Kennan was always the professional, in the sense that there’s nothing in there that’s top secret or secret. He would often say: ‘I talked with so and so,’ without revealing anything substantive. There is very little there about people, particularly when they were alive. He was very discreet. He intended the diary to be read. He was a man of discretion – and with diplomats, that’s their job.”

Kennan also reflected in the diary about his ambitions, perceived failures, and his family relationships and, later in his life, about his physical and intellectual decline.

“He was enormously ambitious, and his constant refrain in the diary is his lamenting of his falling short of those ambitions,” Costigliola says. “There are other people widely respected for their work but who have turbulent inner lives as well. We see the whole picture here from Kennan. I don’t think it takes away from his intellectual achievements at all. We can better see the context of those intellectual achievements by seeing the full person who had those achievements as well as those personal dilemmas.”

The historian says he will continue to study Kennan for his next book project, one focused on the diplomat’s relationship with the Soviet Union, utilizing a research fellowship recently awarded through the Humanities Institute of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

“What I really want to do is go back and read the things that Kennan read about Russia and go down to the archives in Washington and look at the early reports he sent from Moscow,” he says. “I really want to see things through his eyes as much as I can, and talk about his lifelong relationship with Russia.”

To hear Costigliola discuss the book on NPR-affiliate WNYC, click here.