Last week, the woman who discovered BRCA1, a gene that in a mutated form increases vulnerability to breast cancer, received a Lasker Award for her achievements in medical science. Mary-Claire King of the University of Washington, who simultaneously published an article in JAMA about population-based screening for cancer-related genetic mutations, took the opportunity to call for much wider use of genetic screening for breast and ovarian cancer than currently exists. Practitioners now typically recommend this screening only if a woman already has a diagnosis of cancer or a family history of breast or ovarian cancer.

UConn Today asked UConn Health’s genetic counselors Robin Schwartz and Jennifer Stroop, who together have more than 50 years of genetic counseling experience, about the debate surrounding genetic screening for breast cancer.

Q. The woman who discovered BRCA1 is calling for all American women aged 30 years or older to be screened for cancer-causing genetic mutations, regardless of their race or ethnic background. Do you agree with that?

A. Not yet. It is an important and ongoing discussion, and Dr. Mary-Claire King continues to be at the forefront of BRCA research. However, we agree with the president-elect of the National Society of Genetic Counselors, Joy Larsen Haidle, who said, “… it is premature to recommend testing for all American women over the age of 30.” Dr. King’s study in JAMA looked at a specific cohort: Ashkenazi Jewish men living in Israel. Individuals of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewish ancestry have a higher chance of carrying a BRCA mutation. It is difficult to use data from a high-risk population based on ethnicity and apply it to the average person. And, before taking any test, patients need to fully understand how to use the results to make informed health decisions. Genetic counselors are available to help patients and their doctors ensure high quality care, appropriate use of results, and attention to the psychological issues associated with genetic testing.

Q. What is the percentage of women who carry the breast cancer genes?

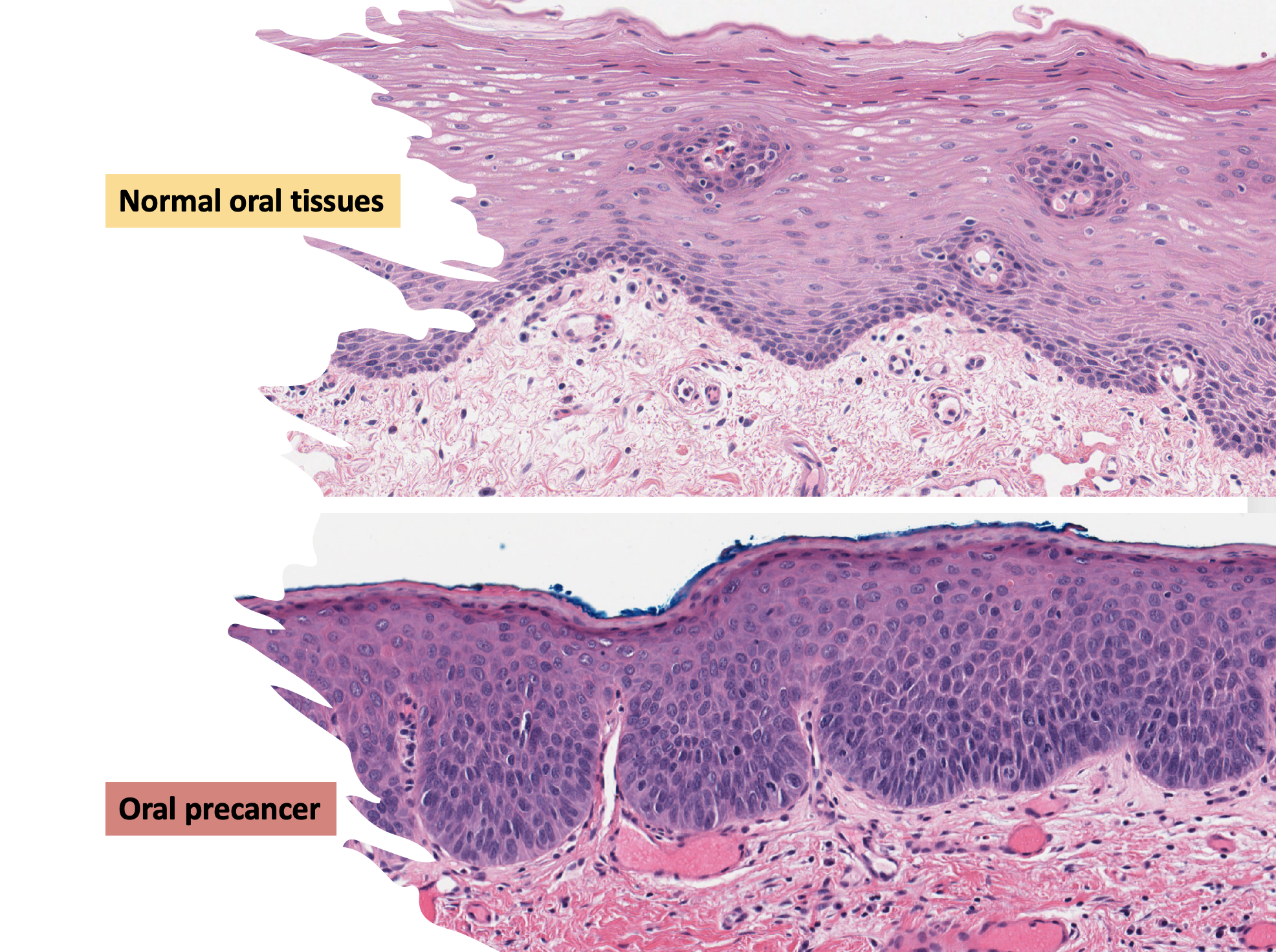

A. In general, approximately 1 in 600 women carry a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Men can carry these mutations as well. Everyone typically has two copies of BRCA1 and BRCA2, which play an important role in the cell as tumor suppressors and DNA repair.

The increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer comes from carrying a mutation in a BRCA gene. Women who carry a BRCA mutation have approximately a 60 to 85 percent lifetime risk for breast cancer, and a 10 to 40 percent risk for ovarian cancer. This is a much higher risk over their lifetime compared to the general population, where it is 12 percent for breast cancer, and 1.5 percent for ovarian cancer. But a positive BRCA test result is not the same as a cancer diagnosis. Women may carry a BRCA mutation throughout their lives and never develop cancer.

Q. In 2013, Angelina Jolie revealed that she had a risk-reducing double mastectomy following genetic testing that showed she was positive for a mutation in one of the cancer predisposition genes. Her story sparked a national discussion about genetic testing. Have you seen an increase in women requesting genetic testing to learn their BRCA status at UConn Health since then – the so-called Angelina Jolie effect?

A. We’ve seen an approximate 20 percent increase in referrals to the UConn Hereditary Cancer Program following Angelina Jolie’s revelation.

Q. Are women overreacting?

A. What becomes lost in the headlines is the idea of individual risk. A recent JAMA study found survival rates similar between lumpectomy – removal of a tumor – and bilateral mastectomy – removal of both breasts, but did not look at BRCA status and whether the individuals had undergone genetic testing.

There is an important discussion still to be had as to whether it is adviseable that women in the general population remove both breasts or whether a lumpectomy is just as effective in treatment of breast cancer. It is important for individuals concerned about their risk for breast cancer to consider genetic counseling prior to genetic testing.

For BRCA carriers, increased surveillance, chemoprevention, and considering a risk-reducing mastectomy, are all options.

To learn more about UConn Health’s genetic services, call 860-523-6424 or visit the Hereditary Cancer Program website: cancer.uchc.edu/treatment/services/cancergenetics.html. The program is part of the Carole and Ray Neag Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Follow UConn Health on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.