Analysis of artifacts from a newly excavated site in Armenia shows that human technological innovation occurred intermittently throughout the Old World, rather than spreading from a single point of origin, as previously thought.

The study, co-authored by UConn archaeology professor Daniel Adler and more than a dozen scientists from universities worldwide, was recently published in the journal Science. Adler and his colleagues examined thousands of stone artifacts retrieved from Nor Geghi 1, a site on the outskirts of Yerevan, the Armenian capital. The artifacts were found in sediments between two ancient layers of lava that could be accurately dated to a period between 325,000 and 350,000 years ago.

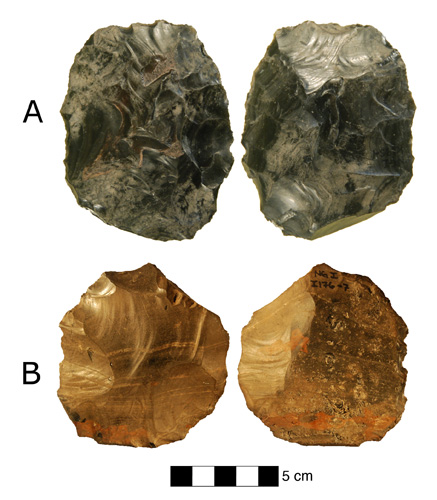

The collection comprises stone tools made using two distinct technologies, an older method called bifacial technology, and a more advanced method known as Levallois technology. Archaeologists previously believed that Levallois technology was invented in Africa and spread to Eurasia with expanding human populations, replacing local biface technologies. The co-existence of the two technologies at Nor Geghi 1 provides the first clear evidence that local populations developed Levallois technology on their own.

“The combination of these different technologies in one place suggests to us that, about 325,000 years ago, people at the site were innovative,” says Adler. Moreover, the chemical analysis of several hundred obsidian artifacts shows that humans at the site utilized obsidian outcrops from as far away as 75 miles, suggesting they must also have been capable of exploiting large, environmentally diverse territories.

The paper argues that biface and Levallois technology, while distinct in many regards, share a common pedigree. In biface technology, a mass of stone is shaped through the removal of flakes from two surfaces in order to produce a tool such as a hand axe. The flakes detached during the manufacture of a biface are treated as waste. In Levallois technology, a mass of stone is shaped through the removal of flakes in order to produce a convex surface from which flakes of predetermined size and shape are detached. The predetermined flakes produced through Levallois technology are the desired products. Archaeologists suggest that Levallois technology is optimal in terms of raw material use and that the predetermined flakes are relatively small and easy to carry. These were important issues for the highly mobile hunter-gatherers of the time.

It is the novel combination of the shaping and flaking systems that distinguishes Levallois from other technologies, and highlights its evolutionary relationship to biface technology. Based on comparisons of archaeological data from sites in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe, the study also demonstrates that this evolution was gradual and intermittent, and that it occurred independently within different human populations who shared a common technological ancestry, says Adler. In other words Levallois technology evolved out of pre-existing biface technology in different places at different times.

This conclusion challenges the view held by some archaeologists that technological change resulted from population expansion during this period.

“If I were to take all the artifacts from the site and show them to an archaeologist, they would immediately begin to categorize them into chronologically distinct groups,” Adler says. The artifacts found at Nor Geghi 1, however, reflect the technological flexibility and variability of a single population during a period of profound human behavioral and biological change. These results highlight the antiquity of the human capacity for innovation.

The excavation at Nor Geghi 1, just outside the Armenian capital of Yerevan, was performed with the help of a number of UConn students, including undergraduates taking part in UConn’s Education Abroad Field School program.

Major support for the work came from UConn’s Norian Armenian Programs Committee, which was established in 2004 to enhance the longstanding collaboration between UConn and Armenia’s Yerevan State University. “The successes of the archaeological field school underscore the importance of high-quality science collaborations with our strategic global partners,” says Daniel Weiner, vice provost for global affairs, who co-chairs the committee.

Additional funding came from the U.K. Natural Environment Research Council; the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation; the Irish Research Council; and the University of Winchester, U.K.