Most people see their pharmacist only when they are dropping off a prescription or picking up medication. But new research by the School of Pharmacy and the Connecticut Pharmacists Association has found that allowing pharmacists to be more involved in the delivery of health care improves patient outcomes and reduces costly emergency room visits.

It is estimated that one in three adults over age 57 takes at least five prescription medications, and half regularly use dietary supplements and over-the-counter drugs that could cause potentially dangerous drug interactions. Medication issues are believed to be responsible for about a third of adverse events leading to hospitalizations.

Many people, for instance, may not be aware that taking the popular blood thinner warfarin along with the cholesterol-lowering drug simvastatin can increase the risk of bleeding. Similar problems may arise when taking warfarin and over-the-counter aspirin or aspirin and ginkgo supplements.

Allowing pharmacists to have greater interaction with doctors and patients helps reduce dangerous medication errors and increases the likelihood that patients will take their medications as prescribed, according to the study, which was made possible through a $5 million grant from the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Connecticut Department of Social Services. The findings were published in April in Health Affairs, a national peer-reviewed journal on health policy thought and research.

Medication therapy management

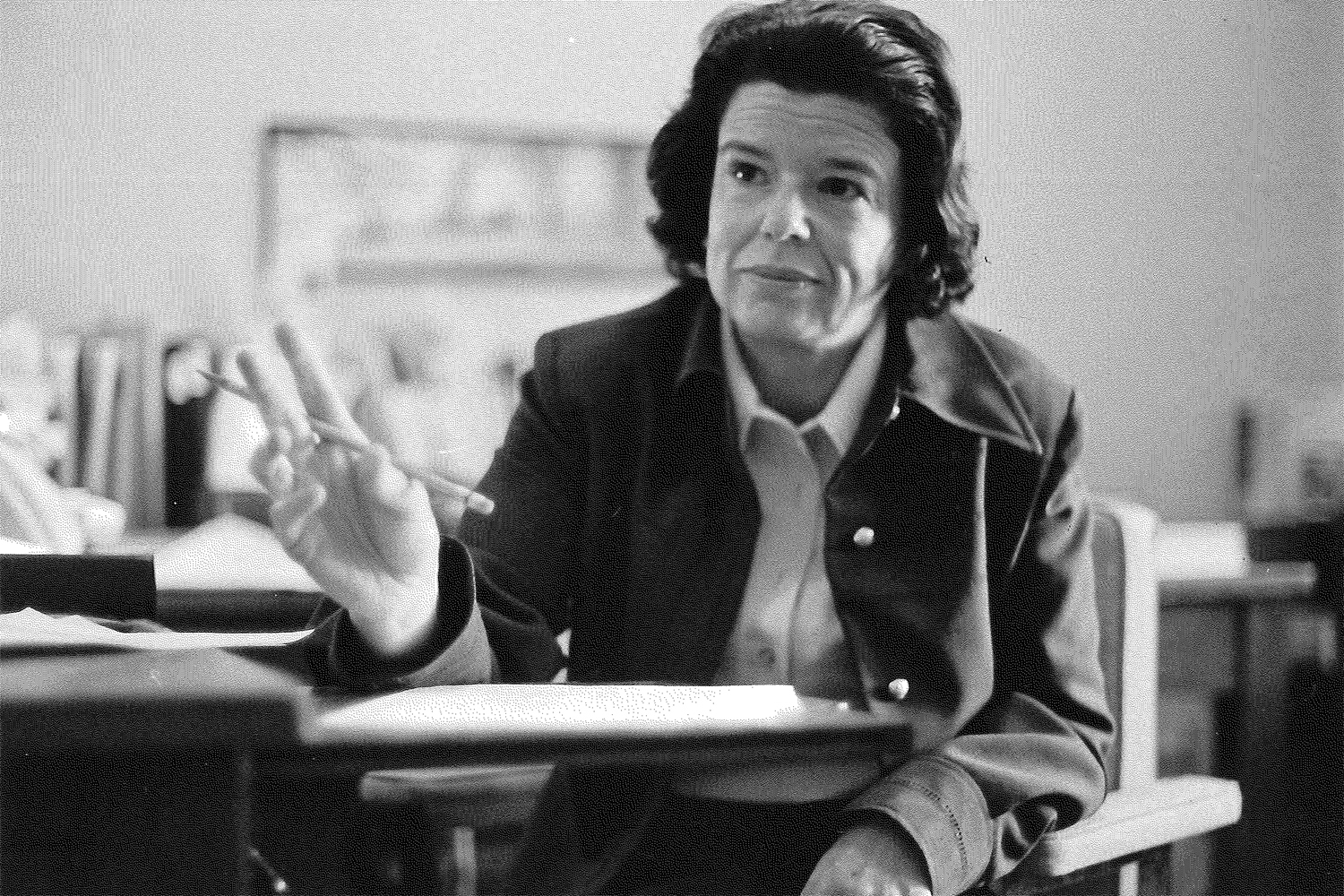

“Medications are a cornerstone of the management of most chronic conditions such as asthma, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes, yet medication discrepancies and medication-related problems—some of which can cause serious harm—are common,” says Marie A. Smith ’77 (PHR), assistant dean for practice and public policy partnerships in the School of Pharmacy and the study’s lead author.

The study recommends pharmacist-supervised medication therapy management as one way of addressing the problem. In medication therapy management, or MTM, pharmacists collect a patient’s health information and assess their medications to identify potential problems such as omission or duplication of medication, dosages that are too high or too low, adverse reactions, issues relating to health literacy, and medication costs. The pharmacist then develops a plan to address any issues that arise and shares it with the patient, along with his or her family members and physician.

In the recent UConn study, a group of pharmacists provided medication therapy management to 89 Medicaid patients over the course of a year. The pharmacists met with patients in their physicians’ offices and had up to five monthly follow-up meetings.

The pharmacists found that 50 percent of the medications being taken by the patients had been discontinued, and 39 percent had a wrong medication name or dose that resulted in discrepancies between the patient’s actual medication use and lists that existed in electronic health records or insurance claim records. By advising patients on prevention options (aspirin to prevent heart attacks, stroke and diabetes; calcium/vitamin D to prevent osteoporosis; and smoking cessation therapy) and by working closely with prescribers in adjusting medications accordingly, the pharmacists increased the ability of patients to achieve their therapeutic goals from 63 percent at the start of the study to 91 percent at the patient’s final visit with his or her pharmacist.

The most common drug therapy problems encountered in the study involved insulin use, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton-pump inhibitors, statins, asthma/COPD inhalers or nebulizers, opioids, steroid inhalers, metformin (for diabetes), and quetiapine (Seroquel).

“The medication lists that are included in electronic health records today often include medications known to a single prescriber only and do not include all medications used by a patient from multiple prescribers, multiple pharmacies, or over-the-counter medications, herbal products, and dietary supplements,” says Smith, a nationally recognized advocate and pioneer in advancing MTM who was recently named UConn’s first Henry A. Palmer Endowed Professor of Community Pharmacy Practice.

Devra Dang, associate clinical professor, and Thomas Buckley ’82 (PHR), ’94 MPH assistant clinical professor, served as co-investigators on the study.

Training tomorrow’s pharmacists

In recognition of today’s rapidly changing health care landscape and the expanding role of pharmacists as partners in the delivery of comprehensive care in what is known as a patient-centered medical home, the UConn School of Pharmacy makes sure its graduates are properly prepared.

UConn students pursuing a six-year Doctor of Pharmacy degree currently are required to take courses in public health, patient communications and cultural competencies, patient assessment skills, and pharmacoeconomics, in addition to classes in biomedical, pharmaceutical, clinical, and sociobehavioral sciences. Students must also participate in multiple clinical rotations.

“Today’s UConn pharmacy graduates are the most well-prepared in our School’s history,” says pharmacy dean Robert L. McCarthy.

“The concept of pharmaceutical care—first described by [Charles D.] Hepler ’60 (PHR) and [Linda M.] Strand over two decades ago, in which pharmacists are not simply responsible for the dispensing of and counseling about medications but are jointly responsible with the prescriber for ensuring the intended outcome of drug therapy—is evident in the rigor and complexity of our professional curriculum,” McCarthy says. “Moreover, our students are prepared to be integral members of an interprofessional health care team caring for patients in a medical home model.”

Smith envisions a future in which community pharmacists have online access to patients’ medical records and are actively involved with physicians in monitoring patients’ care. Pharmacists will continue dispensing medications, but they will also help prevent disease by administering immunizations for such maladies as flu, pneumonia, and shingles.

Until then, Smith continues to work on developing more advanced electronic prescribing systems to alleviate medication errors and to push for greater awareness about the value of pharmacist-provided MTM services. Ultimately, Smith would like to see MTM accepted by health care policymakers and covered by insurance.

“Pharmacists have unique training and expertise to detect, resolve, monitor, and prevent medication-related problems, including medication errors,” Smith says. “Their clinical expertise complements the knowledge and skills of other health care professionals.”