This post is part of a series about the research of faculty members who are seeking to understand the impact of climate change here in Connecticut, and to work toward environmentally sustainable solutions.

The history of land use in Connecticut is one of dramatic but ongoing change. Perhaps most strikingly, the state was once covered in forests that were clear cut to make way for development, and this happened not once, but twice. In addition, significant coastal modification and marsh land changes are now underway, changing the coastline as the sea level continues to rise.

UConn’s Center for Land Use Education and Research (CLEAR) was created to help decision makers make good land use decisions by providing them with the information they need.

The director of CLEAR, extension educator Chester Arnold, says smart land use management is critical in order to preserve open space: “It isn’t something we can go back and fix later on.”

Green spaces provide a wealth of ecosystem services. Forests absorb water and are linked to the health of the watershed, for example, and both forests and coastal wetlands and marshes provide vital habitat for wildlife. Losing green spaces can be devastating for the environment.

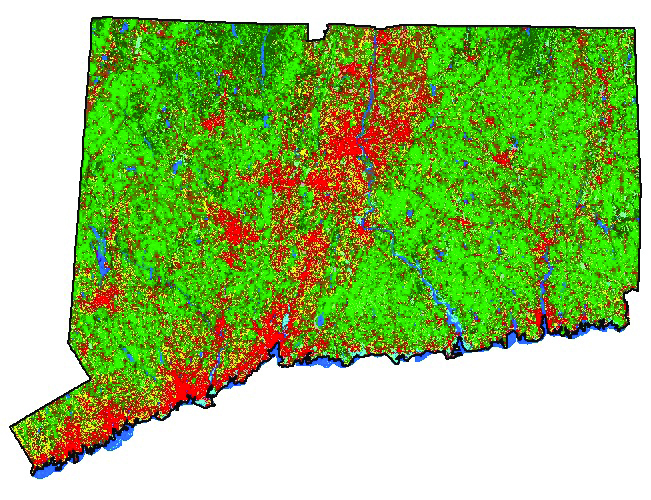

The story of Connecticut’s evolving landscape and changing coastline is told through pictures on the CLEAR website, where decades of data and satellite imagery are pulled together to help visualize changes over time.

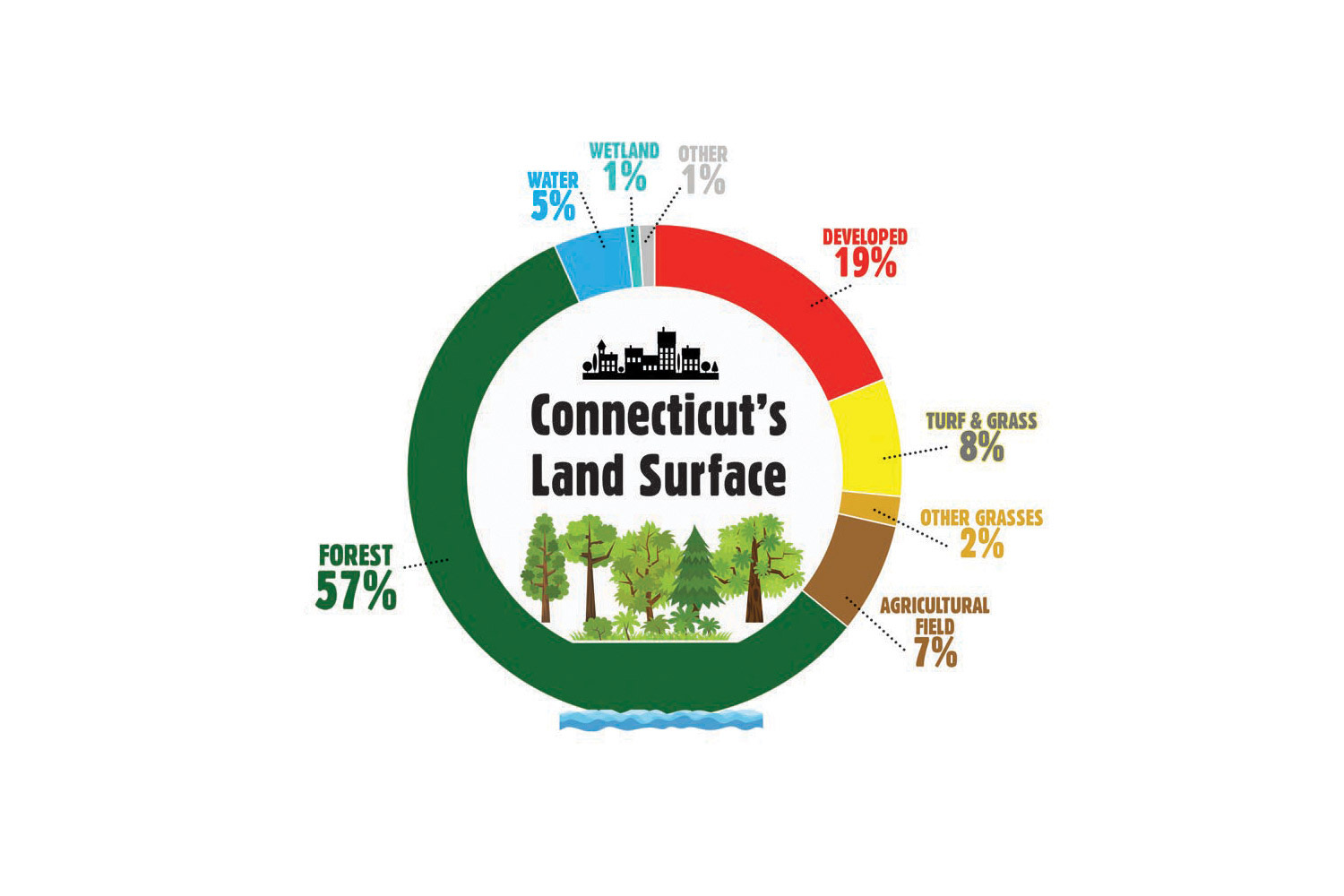

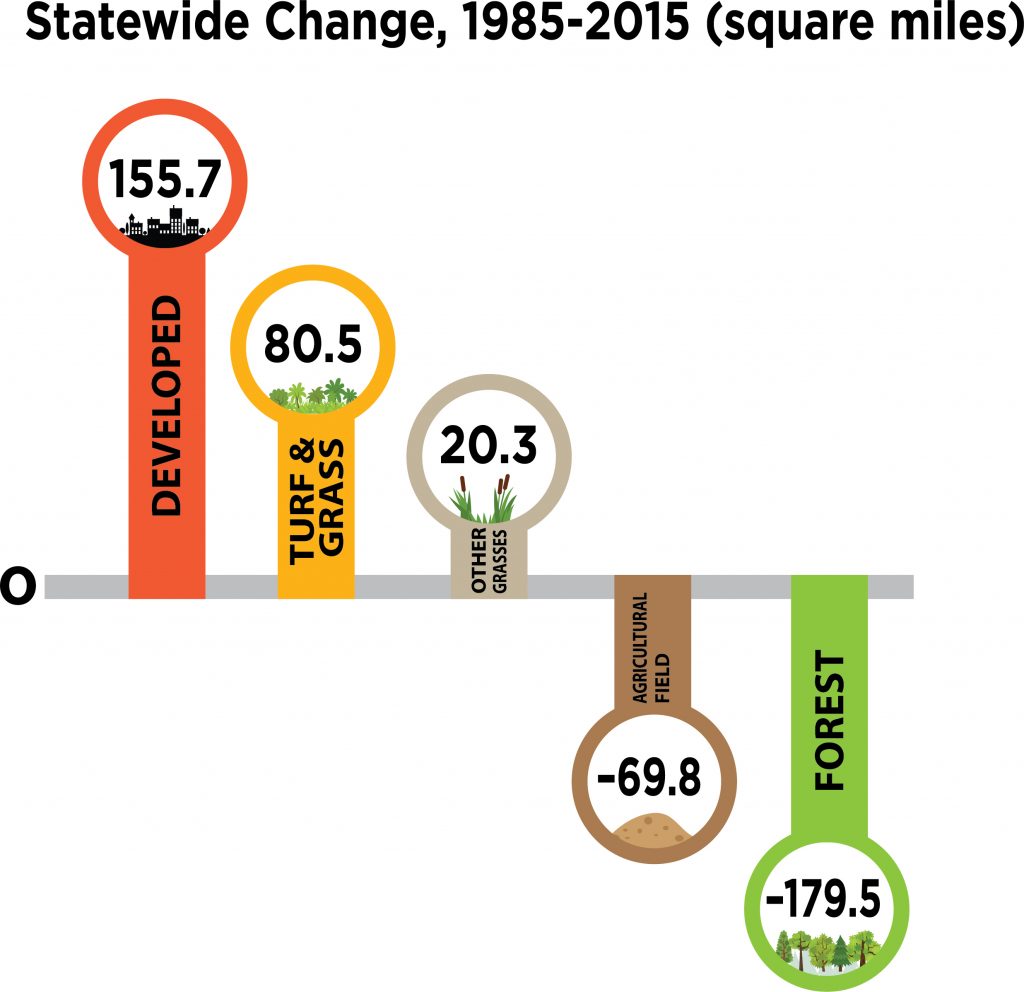

The Connecticut’s Changing Landscape story map, for example, shows that forests are being rapidly lost to development, diseases, and pests. Between the years of 1985 and 2010, Connecticut lost 190 square miles of forest, or the equivalent of 13.3 acres per day. Turf and grass, often described as biodiversity deserts, now cover more of Connecticut than agricultural fields, which are being lost at a rate of more than four acres per day. And each day, 10 additional acres go under development in the state.

Addressing land use at the local level

Connecticut has 169 separate municipalities, each of which is largely responsible for land use decisions within its boundaries. Those serving on planning and zoning commissions within the municipalities are volunteers, and the state does not currently have any mandated training for those volunteers. Beyond the municipalities, Arnold says, there is no statewide office of planning whose primary role is to determine how land is used. The bottom line is that decisions about land use come down to each town’s planning and zoning commissions.

CLEAR aims to provide useful resources for Connecticut communities. The organization’s land cover data, for example, provides local land use commissions with a detailed view of how and where their town has changed since 1985. Arnold says he hopes that seeing data about what has happened in the past will help shape future decisions.

Development tends to follow what is happening with the economy, he says, a trend that was apparent in the late 1980s, when there was a high rate of land use change, as forest or farmland was put under development. And now, with similar reports of economic recovery, there may be a burst of land conversion as a result, leading to further erosion of green spaces.

Arnold says whether or not funding and policies to help direct development and conservation are in place at the state level, it’s important to remember that almost all the action happens at the town level, and that’s where efforts to affect land use policies and practices need to focus.

He recommends three ways citizens can help ensure land is used and protected wisely:

-

- Get involved in local planning and zoning commissions;

- Educate yourself and others about land use concerns; and

- Support land trusts.

Arnold says private, non-profit land trusts do great work in conservation. As budget cuts hit state-funded conservation efforts hard, these trusts have become the leaders in preservation of green spaces.

“Land trusts are doing a great job,” he says, “they just need more help so they can do an even better job.”

CLEAR also supports land trusts by collaborating with the Connecticut Land Conservation Council to provide training on smart phone GPS mapping for land trust volunteers; and by working with land trusts on the Natural Resource Conservation Academy to create programs and opportunities to train young people as the conservationists of tomorrow.

To learn more about ways you can support open space conservation, visit the CLEAR story map gallery and other resources available through the CLEAR website.

This post is part of a series about the effects of climate change on Connecticut. Other posts in the series include: Connecticut’s Forests Today a Far Cry from Towering Giants of Old; Camera Traps, Citizen Science, Help Track State’s Animal Populations; and Working Toward Sustainable Solutions.

Listen to the writer, Elaina Hancock, discussing the climate change series with the UConn 360 podcast: