“Why do we want to see murdered bodies in stories?” muses Pam Bedore, associate professor of English at UConn Avery Point. “Is it something horrible about human nature? Is it a way we solve puzzles in our minds? Or is it just a way that we process the world, process questions of power?”

Today’s fans of crime fiction will recognize this fascination with sordid tales of murder, mystery, and mayhem. But the genre has deep roots in history, long predating the plethora of police procedurals that grace our TV screens today.

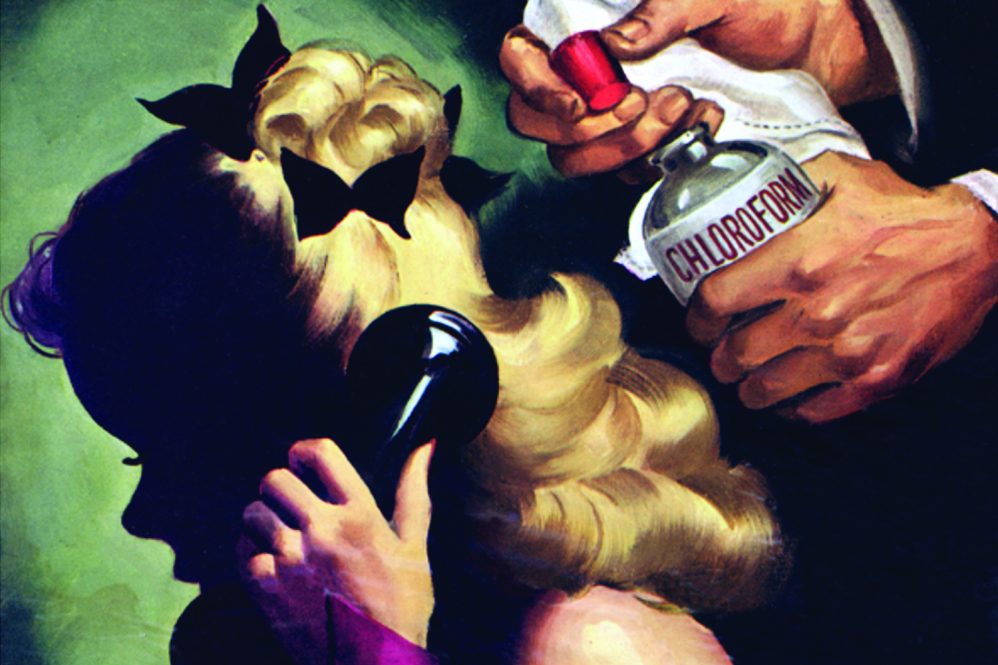

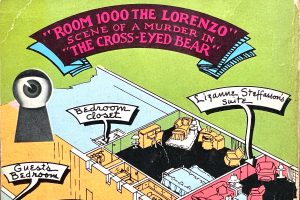

Between the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, crime fiction experienced a golden age of popularity thanks to the cheap and widely available formats of dime novels and, later, pulp magazines and paperbacks. The aesthetics of these publications, from cover art to plot devices, have remained hugely influential in all forms of storytelling.

Bedore and Alison Paul, associate professor of illustration and animation, are interested in uncovering the role of women creators and characters in the history of this genre.

The two professors are planning a fall 2027 exhibition at the William Benton Museum of Art entitled “Damsels, Femme Fatales, and Queens of Crime: Feminism and the Golden Age of Detective Fiction.”

With funding awarded by UConn’s Office of the Vice President for Research – $2,000 from the Scholarship Facilitation Fund (SFF) and $5,344 from the Scholarship and Collaboration in Humanities and Arts Research Program (SCHARP) — they are traveling to archives and museums to do research and identify materials for the exhibition.

The exhibition will be available for viewing by all visitors to the Benton, and Paul will also teach a class that uses the exhibition as its central text.

The Mystery of the Missing Masterminds

“Of course, there’s an escapist part to our love of detective fiction,” Bedore says. “But there is also a lot of analysis of power in this genre. It’s threefold — the power plays within these stories, the power plays in the visuals, and the power plays in the publishing world that were happening at the time.”

Detective fiction has long been dominated by male writers and artists. From an archivistic standpoint, too, the skew toward men presents a research issue – most of the surviving copies of dime and pulp novels come from private collectors, who may not have prioritized buying books written or illustrated by women. But Paul and Bedore, who combine the disciplines of art and English, are doing some sleuthing of their own.

“Damsels, Femme Fatales, and Queens of Crime” will center on cover art from twentieth-century pulp magazines and paperbacks, seeking to unearth and contextualize the work of women artists. It will provide patrons with “an immersive experience of how women pervaded the male-dominated genre of crime and detection fiction in the early and mid-20th century,” Paul and Bedore say, “organized thematically around character tropes that invite viewers to consider whether they are confirming, challenging, or complicating existing norms around gender and sexuality.”

“My students want to be illustrators,” says Paul, who teaches in the Department of Art and Art History. “When they look at this ‘golden age’ … it’s a lot of straight white males producing the work, and the imagery itself is really misogynistic and often racist. I want to be able to show this stuff and talk about what’s so successful about these images to my students, but give them some context. What was happening at this time? Why was this imagery so prevalent?”

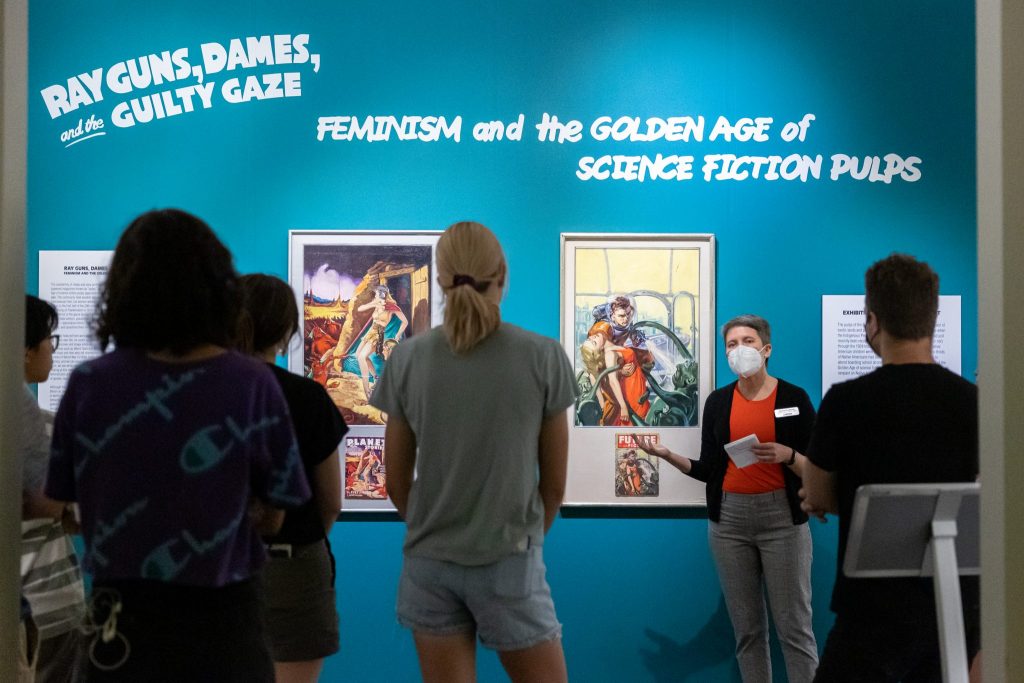

Paul has some previous experience bringing pulp art to the masses. In 2022, she co-curated another exhibition at the William Benton Museum (along with associate professor-in-residence Barbara Gurr) entitled “Ray Guns, Dames, and the Guilty Gaze: Feminism and the Golden Age of Science Fiction Pulps.”

Like “Damsels,” “Ray Guns” grappled with the fact that the so-called “Golden Age” of a particular style of illustration was also deeply embedded with misogyny and racism. This showcase examined the visual tropes of science fiction art in the mid-twentieth century.

“I was ready to level up,” Paul says about her next exhibition. “We got the main gallery space, so we can add in film and costume in addition to the original pulp art covers. We can really dig a little deeper, using what I learned from the first show.”

Turning on a Dime

For Bedore, too, this project will engage one of her academic passions – crime fiction as a lens into cultural narratives, ideologies, and anxieties.

Dime novels emerged as a focus for Bedore by chance, when she was a Ph.D. student at the University of Rochester. While she walked into the library one day seeking resources for a completely different research question, she was introduced to the university’s collection of over 10,000 dime novels – one of the largest in the country. She left the library with the strange sense that the trajectory of her life had just shifted.

Since then, Bedore has become one of the world’s foremost experts on dime novels. For this project, she says, “I’ve read over 100 dime novels from start to finish with attention to how they’re functioning – what their rhetorical purposes are, how they’re appealing to people. And because they’re detective novels, I’ve also studied, what does the killer look like? What does the victim look like? What does the detective look like?”

Representation for women within these books was slim – but still present, Bedore points out.

“In a sample of 100, we had four women detectives,” she says. “It’s a tiny number, but it’s not nothing. And those women detectives are super interesting.”

Bedore and Paul are drawing on the special collections at the University of Rochester library as they compile this exhibit. They are also borrowing from the collections at the New Britain Museum of Art (which houses the Robert Lesser collection of pulp novel cover art, featuring the original full-size oil paintings), Syracuse University, and the University at Buffalo. The SFF grant supported their travel to these archives.

In addition to introducing the broader UConn and Connecticut communities to the historic work of women in detective fiction, “Damsels” will also provide a once-in-a-lifetime learning experience for Paul’s illustration students, blending an appreciation for art with an understanding of the thorny history that produced it.

“The majority of my students are female, and/or queer, and/or students of color,” says Paul. “If this is my student body, how can we look at these histories in class? I always think it’s important to remember, it’s not like women weren’t there doing this stuff, or creators of color, or closeted queer creators (which we’ve found a few of). Connecting it to the students has always been the main goal.”