The picturesque views of lush forest and rolling hills for which Horsebarn Hill is known are in for a big change over the next several years. Changes are already evident, with signs that an invader has arrived: the Emerald Ash Borer.

Though attractive in appearance – it belongs to a family known as jewel beetles – this small, shiny insect’s arrival is very bad news for ash trees.

After hatching from inconspicuous eggs laid on the tree’s trunk, Borer larvae chew their way through the tree’s actively growing outer layer just beneath the bark, an area called the cambium. This is the layer that gives rise to the annual growth rings, and it is vital for the transportation of water and nutrients throughout the tree. This tunneling cuts circulation to areas of the tree both above and below the damaged tissues; and if enough larvae feed on a tree at once, the tree can die in as little as two years.

The adult Borers are only 3/8 to 1/2 inch long, 1/16 inch wide, and live for just three to six weeks; they are rarely seen. The larvae are 1½ to 2 inches long, and feed on ash bark for one to two years.

The Emerald Ash Borer is native to northeastern Asia. Since it was first detected in North America in 2002, it has left millions of dead trees in its wake as it spread across the country, finally arriving in Connecticut in 2012.

“The Ash Borer has devastated the ash population,” says University arborist John Kehoe. “Until recently, the Borer hadn’t been reported in Mansfield, but it’s making an impact now. We especially need to watch out in the UConn Forest.”

Most of the trees seen from Horsebarn Hill are in a part of the UConn Forest known as the Fenton Tract, where specimens of ash range from the occasional individual tree to as much as half of the canopy in some places.

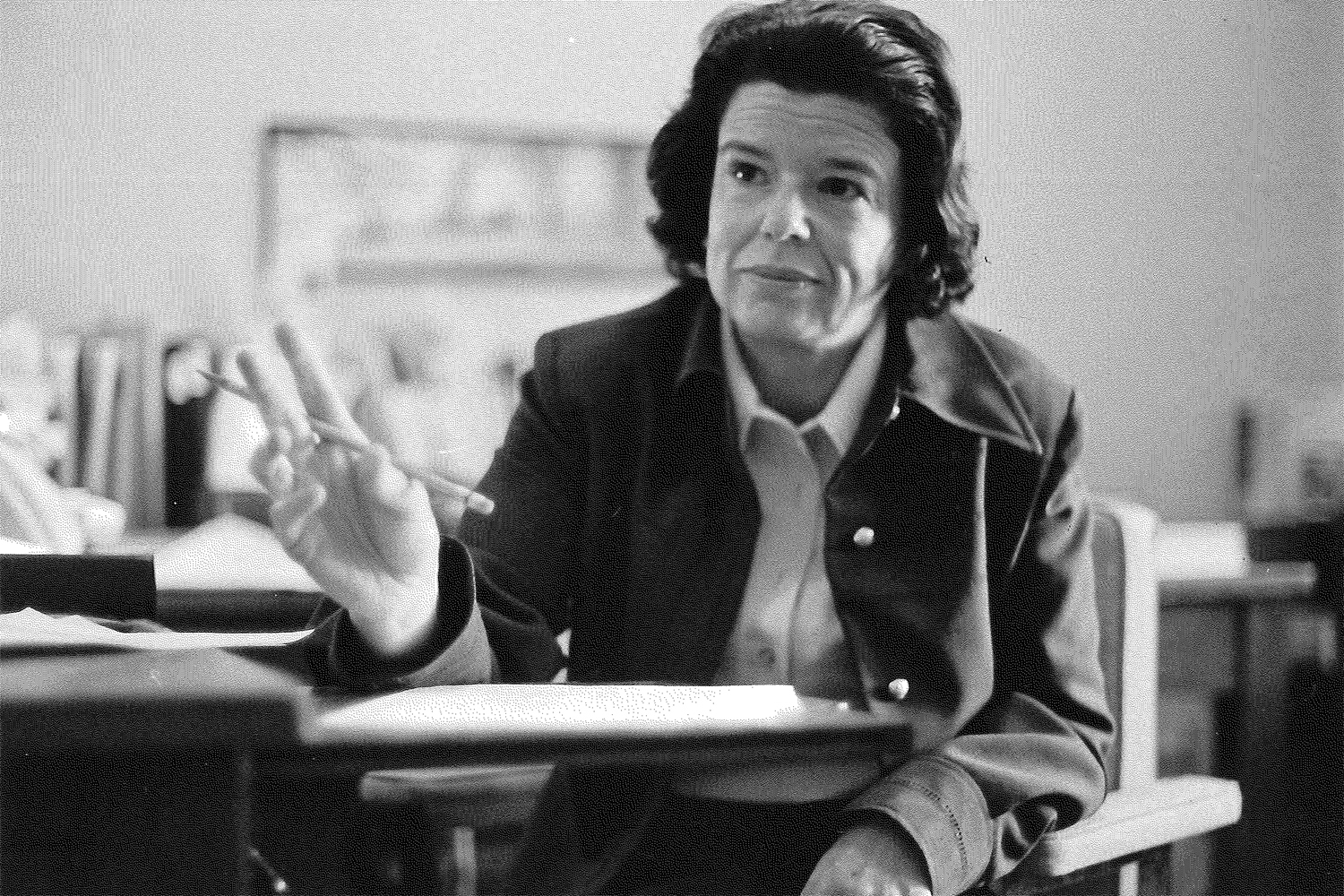

Thomas Worthley, associate professor of extension in the College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources and chair of the UConn Forest Management Committee, says the Fenton Tract is the most regularly used part of the UConn Forest for recreational purposes. It hosts an extensive network of trails that take hikers, trail runners, and bicyclists through various forest ecosystems.

Beyond its recreational value, the Forest serves as a living laboratory, closely mimicking conditions in forests owned by private land owners. UConn students play a vital role in maintaining the Forest. As part of the Forestry Crew, they map and document tree species; fell trees marked for removal; and process the wood from felled trees.

With such a significant proportion of the trees in the Forest under threat from the Emerald Ash Borer, difficult and labor-intensive forest management decisions are on the horizon. If measures aren’t taken, dead and dying ash trees could become hazardous for those who venture into the Forest.

“Ash trees don’t stand up well against the weather after the tree dies,” says Worthley. “Watch out for falling limbs.”

One option, and perhaps the easiest, is to fully harvest the existing ash trees ahead of an infestation, knowing the trees will need to be removed eventually anyway. Ash has long been viewed as a valuable wood, for everything from furniture to baseball bats, but it is only valuable as long as the trees supplying the lumber are alive, Worthley says.

Instead, he and the Forestry Crew have taken a more gradual approach. They began by thinning trees in an area of the Forest that had sustained damage a few years ago, when a microburst ripped through the Fenton Tract, twisting and uprooting a number of trees along its path. The damage caused by this storm provided a perfect opportunity to begin experimenting with Emerald Ash Borer management strategies.

The Forestry Crew removed the damaged trees, which included some ash, and thinned others, trying to leave the healthiest trees and be strategic with removal. These measure have meant that other species, such as maple, oak, and hickory, have begun to flourish, filling the gaps in the canopy once dominated by the ash trees and resulting in more diversity overall. A downside has been that the extra light enabled invasive species of undergrowth plants, such as Japanese barberry and bittersweet, to proliferate.

“You try to address one management issue and then you have to deal with another one,” says Worthley, noting that the invasives will need to be treated to ensure that native species are able to become established.

The success of this early thinning process highlights perhaps the only silver lining of the Emerald Ash Borer’s arrival – change. Worthley says change is not necessarily a bad thing for forests: “The Forest has matured, and as conditions change, we see different species. To encourage diversity, we need to support younger forest systems as well as mature ones.”

Fortunately around the main campus, the ash trees have been faring well so far. However, University arborists are keeping a close eye on the situation and have administered annual preventive treatments to protect the many notable specimen ash trees, including the beautiful, old tree beside the UConn sign on Route 195, across from Moulton Road, on the approach to campus from the north.

Homeowners should also keep an eye on any ash trees they may have. Bill Bates, another University arborist, recommends looking for wilted leaves and woodpecker damage on the tree limbs or trunk, as both are possible signs of Emerald Ash Borer activity. If an infestation is suspected, it’s best to call an arborist who can treat the tree appropriately. In addition, the UConn Center for Land Use Education and Research (CLEAR) encourages anyone who finds the insect or evidence of an infestation to inform the state entomologist.

The outlook for individual ash trees is more hopeful than for those that are clustered in a forest. “Treating individual trees on campus is fairly inexpensive, but in the case of thousands of trees, like in the UConn Forest, it simply isn’t feasible,” says arborist Kehoe. “We’ll have to see what happens. Hopefully a biological control will come along, like we saw with the fungus for the gyspy moths.”

In the meantime, enjoy the views as they are, for as long as they exist.

On Saturday, Oct. 14, from 9 to 11 a.m., Worthley will lead a hike for members of the public in the Chaffeeville Tract of the UConn Forest. For information and to register, go to http://s.uconn.edu/ucforesthike.