The success of the fall harvest has been a life-and-death event for our ancestors since the first seeds were sowed about 10,000 years ago in the Near East. It is not surprising that, across the globe, many important events of the year coincide with the harvest, including in North America, where we mark the harvest by celebrating Thanksgiving as a sumptuous feast.

The centrality of the feast in human gatherings, however, extends far beyond harvest festivals to major holidays and the marking of important life events. Special meals form not only the centerpiece of religious holidays, such as Christmas, Passover, and Eid al-Fitr, which ends Ramadan, but also of weddings, graduations, birthday parties, and funerals. The integration of feasts and special events is universal across human cultures.

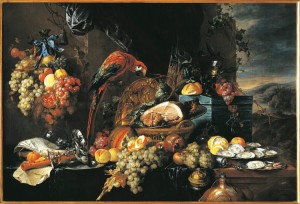

So what exactly is a feast? A feast is a large and elaborate meal set apart from everyday dining in its size and investment and expressed in the use of special foods prepared in distinctive ways, often steeped in traditions that require significant time and resources. The foods—perhaps a favorite family recipe for cranberry sauce—also may be served using treasured tableware, such as Grandma’s china.

The social side of feasting

At their most obvious, feasts serve to provision guests and to celebrate or commemorate special events. Feasts, however, also play much more subtle social roles. In particular, they serve as a social glue that holds communities together by smoothing tensions, forging alliances, creating shared memories, and exchanging information.

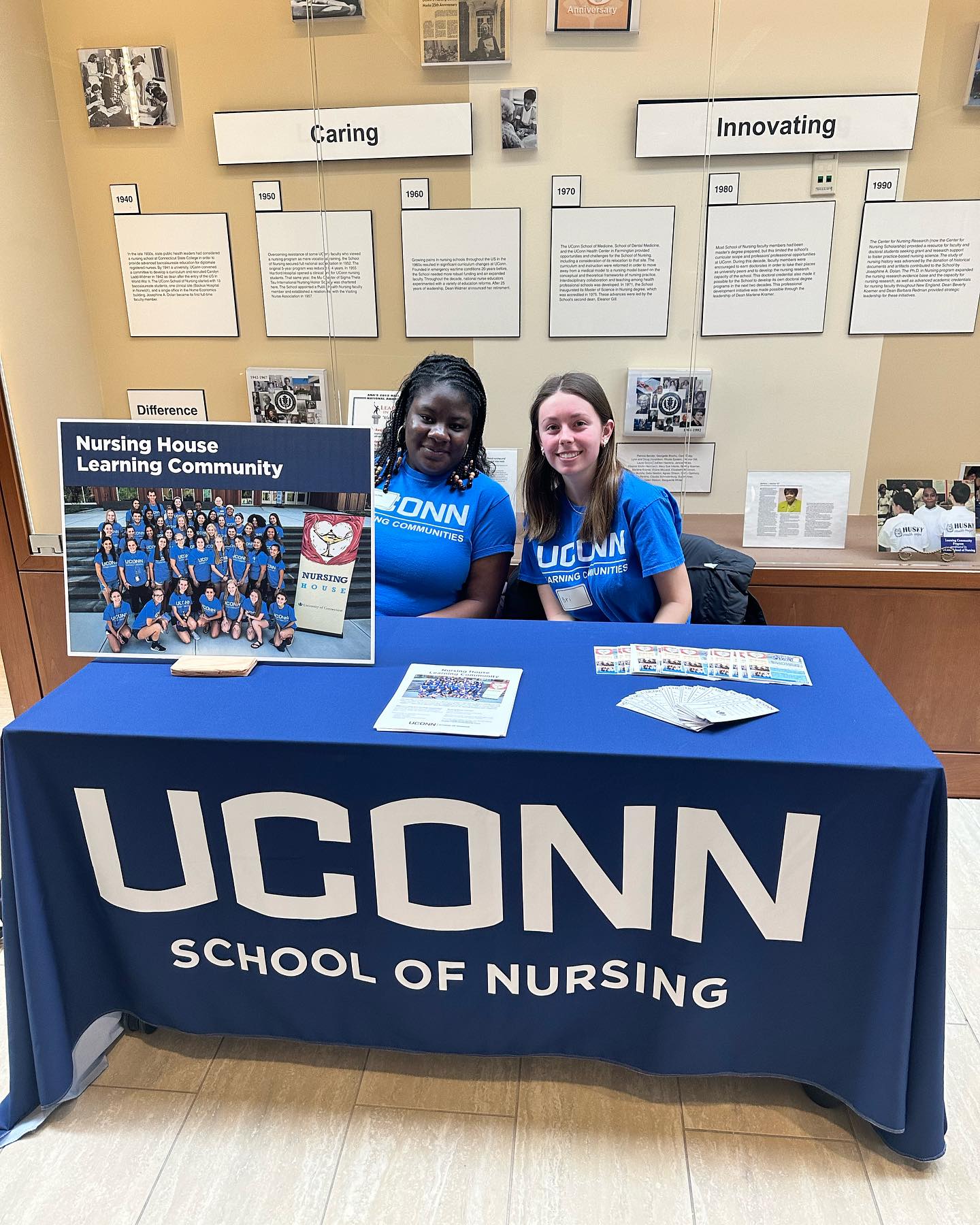

An example at UConn is Midnight Breakfast, a “feast” that takes place to treat students before final exams. The meal is special because of the untraditional time of the event and because the type of food available is not typically consumed at night. In addition, students are served by faculty and staff, who volunteer for the event. The breakfast creates a sense of community by flipping the traditional relationship between staff and students, promoting camaraderie, and allowing these groups to mingle in a relaxed setting atypical of everyday interactions.

Given how deeply ingrained feasting is in modern human cultures and the significance of its social role, it may be surprising that until recently no compelling evidence for feasting prior to about 10,000 years ago existed.

Over the past decade, serving as an excavator and analyst of animal remains (bones and teeth) at the site of Hilazon Tachtit, a burial cave in the Galilee of Israel, I have uncovered evidence of feasting further back in history. The cave was in use around 12,000 years ago, when humans still hunted and gathered for a living. These folks were the first groups to settle down into more or less permanent communities and intensively harvest and process cereal grains, such as wheat, that now provide the foundation of our modern economy.

At least 28 individuals were buried at Hilazon Tachtit. One of these was an unusual older woman laid to rest in a specially prepared grave plastered with stone slabs and clay, accompanied by a variety of unusual animal remains. The animal parts included a leopard pelvis, a wild cow’s tail, the wing tip of a golden eagle, the skulls of two martens, and the shells of at least 70 tortoises. A variety of lines of evidence—including tool marks, bone fractures, and burning patterns—tells us that the tortoises were roasted in their shells and then cracked open. The butchers removed the meat carefully so that the top of the shell was left whole. All of this happened at the time of burial, and then the tortoise remains were buried with the woman in her grave.

At least 28 individuals were buried at Hilazon Tachtit. One of these was an unusual older woman laid to rest in a specially prepared grave plastered with stone slabs and clay, accompanied by a variety of unusual animal remains. The animal parts included a leopard pelvis, a wild cow’s tail, the wing tip of a golden eagle, the skulls of two martens, and the shells of at least 70 tortoises. A variety of lines of evidence—including tool marks, bone fractures, and burning patterns—tells us that the tortoises were roasted in their shells and then cracked open. The butchers removed the meat carefully so that the top of the shell was left whole. All of this happened at the time of burial, and then the tortoise remains were buried with the woman in her grave.

The site of a neighboring structure, meanwhile, has provided evidence of a second large feast, on wild cattle. The skeletal remains from at least three wild cows indicated that the meat had been removed using stone tools, and the marrow cavities breached to remove the valuable fat within. Adjacent limb bones were tossed into the fill when still bound by connective tissue, indicating that the bones were fresh when buried. Like the tortoises, the cattle bones provide evidence for the consumption of vast quantities of meat—enough for at least 2,000 half-pound hamburgers!

This is of particular interest, given the rarity of these animals in contemporary human sites. Although an intact human burial rests on top of the cattle bones, it is impossible to know whether the cattle feast accompanied the burial of this individual or another person in the cave. Nevertheless, the tortoise and cattle remains found in the two structures attest to the importance of feasting at funerals, even at the very beginnings of the shift toward an agricultural lifestyle.

The beginnings of community

Given the universality of feasts at important events today, we might expect to find them 12,000 years ago in a burial cave in Israel. After all, feasting at funerals or near the graves of the dead are central to modern-day events, such as the Irish wake or the Mexican Day of the Dead. The items left at Hilazon Tachtit indicate that people visited this place specifically to bury their dead. In some cases the funerals were invested, signifying the respect that these people had for death.

Nevertheless, the site of Hilazon Tachtit provides the earliest evidence for a feast recovered to date. So why, even if people were feasting prior to this, do we first start to find the evidence for feasts at this juncture of human history?

I believe that it is because the site of Hilazon Tachtit came into use near the beginning of a period of profound social and economic change that culminated in the origins of agriculture. Heading down the pathway toward an agricultural lifestyle marked a point of no return for these hunter-gatherers. The intensive harvest of cereal grains and other wild plants and animals led people to settle into more permanent villages, which was fraught with new tensions caused by dramatic increases in interpersonal contact among community members. These folks needed new mechanisms to iron out everyday conflicts that arose under crowded living conditions, and new experiences from which to develop a shared sense of pride and belonging to their community.

These are the kinds of roles that feasts continue to play even today. So this year when you sit down to Thanksgiving dinner, you need not worry when Auntie Marie and Grandpa start to quibble. Remember that you are in fact engaging in an important ritual feast that will strengthen social bonds and ultimately produce a more effective and cooperative community.

Natalie Munro is an associate professor of anthropology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.