Getting radiation treatment for breast cancer can make you feel vulnerable. Sitting in a machine with radiation pointed directly at your chest, you have to trust that the doctor knows what he or she is doing, that the x-rays are aimed right, that the machine is properly calibrated … and then you just sit perfectly still.

But what if you could have some control over the process?

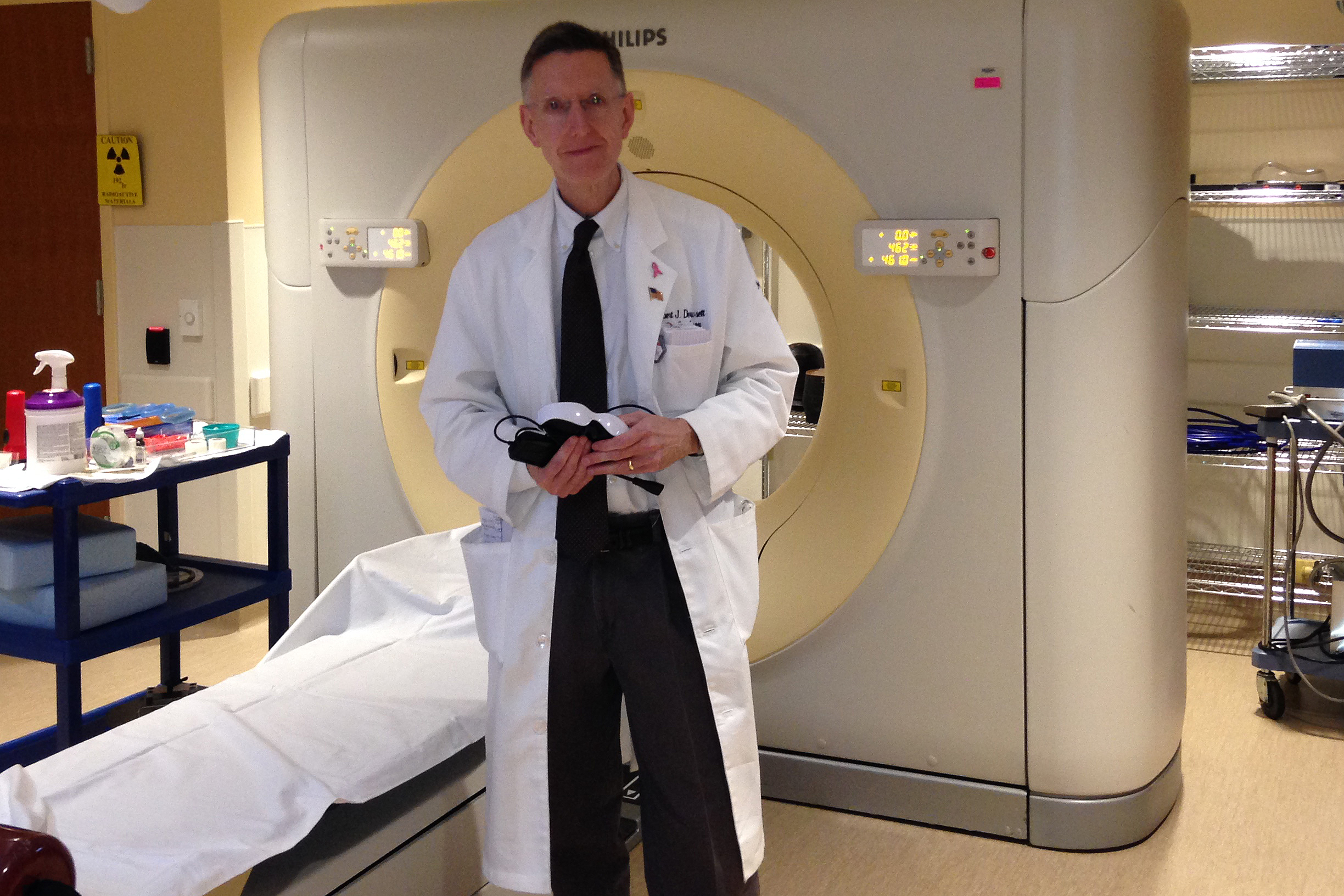

In the Neag Comprehensive Cancer Center at UConn Health, division chief of radiation oncology Rob Dowsett and his colleagues are using a new technique that gives breast cancer patients some agency in their radiation treatment. And they’re taking better care of the patient’s heart in the process.

Using the technique, called Deep Inspiration Breath Hold, patients can help control the accuracy and timing of their own radiation dose. The patient takes a deep breath of specific depth before the radiation machine turns on. Doing this correctly can increase the distance between the heart and the breast by a centimeter or two, lowering the amount of radiation hitting the heart by as much as 50 percent.

Sixty-two-year-old Jeryl Dickson was one of the first patients at UConn Health to use the technique, from late 2015 through early February of this year. Her doctors, including Dowsett, prescribed a course of radiation therapy to make sure there were no lingering cancer cells remaining after a lumpectomy removed her breast cancer.

Radiation treatment of breast cancer can be very effective, eradicating tumor cells hiding in the chest wall. But breast cancer survivors have a heightened risk of heart disease that may show itself years later. Ironically, the heart disease stems from the radiation that originally saved their lives. Radiation is a type of light, and like visible light, it has a tendency to reflect and scatter. Just as even the sharpest spotlight has blurred edges where it blends into shadow, even the best-aimed medical radiation beam occasionally scatters into tissue outside of the tumor it targets. Sometimes it hits the heart.

“We worry about heart attacks down the road, 10 to 15 years after radiation treatment of cancer in the chest. We also worry about inflammation on the outside of the heart in the short term,” says Dowsett. “We don’t exactly know how the radiation damages the tissue, but it definitely seems to accelerate damage to blood vessels. It can also cause scarring and fibrosis damage.”

Not only does the distance between the heart and the chest wall vary from person to person, but a patient can intentionally increase that distance by controlling her breathing using the Deep Inspiration Breath Hold.

UConn Health’s DIBH technology, powered by C-RAD, works by synchronizing the radiation beam’s delivery with a patient’s breathing. The scanning system is essentially a computer with a camera that models the surface of the skin on the patient’s chest. It tracks the patient’s breathing, and coaches her to inhale just the right amount. As the patient, you see a bar graph showing your inhalation, with a box at the top. Your goal is to hit the box and then hold your breath for the 20 to 30 seconds it takes to complete the radiation treatment. Some patients can hold their breath that long; others find it more difficult. It doesn’t matter, because if you exhale, or giggle, or cough, the system sees your chest move out of the perfect range and stops the radiation. It won’t restart until you get yourself back in position and inhale to just the right spot again.

UConn Health is the only hospital using this technology in Central Connecticut. It’s a powerful, precise way to make sure the radiation beam gets the cancer, and minimize the risk to other organs.

Previously, “the area we treated inevitably ended up being bigger than the target tumor itself,” Dowsett says. “Now, we’ve expanded this technique to abdominal targets such as the pancreas and adrenal lesions,” while sparing healthy surrounding organs.

To learn more about radiation oncology services at UConn Health, go to the Neag Comprehensive Cancer Center website or call 860-679-3225.